Making awkward human interactions even more awkward and less human

Yesterday we talked about how AI can act unethically, as well as encourage and enable humans to engage in unethical behaviour.

The idea that technology enables us to do things is self-evident, yet the inverse is also true, that technology enables us to not do things.

Manual labour is an obvious example of something that technology enables us not to do. What if the same were true for emotional labour?

Manual labour is difficult, and tiring. Emotional labour is also difficult, and tiring.

Especially for companies who are more concerned with liability and efficiency than the emotional well being of their contractors or soon to be former contractors.

This story is not the first, nor the last, but it is evocative of our present, a kind of zeitgeist.

“There are a lot of things the algorithms don't take into consideration and the right hand doesn’t know what the left hand is doing”

— Jordyn Holman (@JordynJournals) June 28, 2021

Tech promises to make life more efficient, but it can have devastating effects for workers. Read this from @spencersoper https://t.co/2uTF18AMHF

Normandin says Amazon punished him for things beyond his control that prevented him from completing his deliveries, such as locked apartment complexes. He said he took the termination hard and, priding himself on a strong work ethic, recalled that during his military career he helped cook for 250,000 Vietnamese refugees at Fort Chaffee in Arkansas.

“I’m an old-school kind of guy, and I give every job 110%,” he said. “This really upset me because we're talking about my reputation. They say I didn’t do the job when I know damn well I did.”

Normandin’s experience is a twist on the decades-old prediction that robots will replace workers. At Amazon, machines are often the boss—hiring, rating and firingmillions of people with little or no human oversight.

I tend to avoid quoting from Bloomberg articles as they distrust robots so much that they do not embed nicely here on substack. Nonetheless this is an interesting article that plays on the idea that robots will replace workers.

We’ve often dismissed that as myth, but the idea that robots will replace managers is quite realistic and dystopian.

Especially when human workers can be treated as both disposable and in abundance.

Fired by Algorithm at Amazonhttps://t.co/mGX6pXyild @spencersoper pic.twitter.com/ffYmgggFt4

— David McLaughlin (@damclaugh) June 28, 2021

Amazon started its gig-style Flex delivery service in 2015, and the army of contract drivers quickly became a critical part of the company’s delivery machine. Typically, Flex drivers handle packages that haven’t been loaded on an Amazon van before the driver leaves. Rather than making the customer wait, Flex drivers ensure the packages are delivered the same day. They also handle a large number of same-day grocery deliveries from Amazon’s Whole Foods Market chain. Flex drivers helped keep Amazon humming during the pandemic and were only too happy to earn about $25 an hour shuttling packages after their Uber and Lyft gigs dried up.

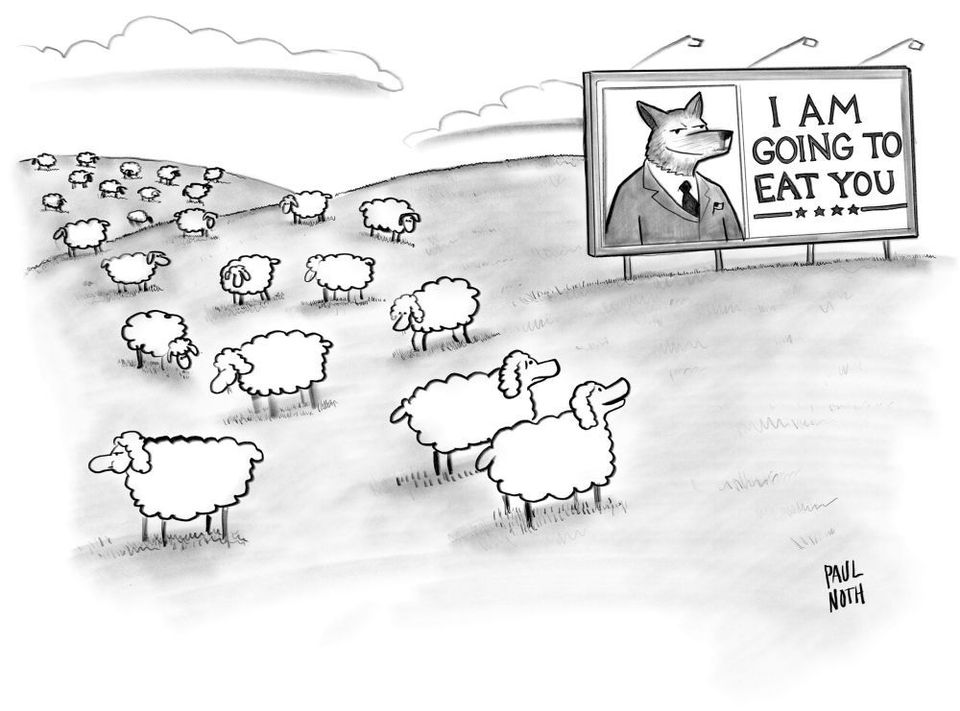

But the moment they sign on, Flex drivers discover algorithms are monitoring their every move. Did they get to the delivery station when they said they would? Did they complete their route in the prescribed window? Did they leave a package in full view of porch pirates instead of hidden behind a planter as requested? Amazon algorithms scan the gusher of incoming data for performance patterns and decide which drivers get more routes and which are deactivated. Human feedback is rare. Drivers occasionally receive automated emails, but mostly they’re left to obsess about their ratings, which include four categories: Fantastic, Great, Fair or At Risk.

Bloomberg interviewed 15 Flex drivers, including four who say they were wrongly terminated, as well as former Amazon managers who say the largely automated system is insufficiently attuned to the real-world challenges drivers face every day. Amazon knew delegating work to machines would lead to mistakes and damaging headlines, these former managers said, but decided it was cheaper to trust the algorithms than pay people to investigate mistaken firings so long as the drivers could be replaced easily.

Amazon is not alone in this approach, although they probably do it at a scale that is unprecedented.

Similarly while this coverage is meant to name and shame Amazon for using such tactics, I fear that it follows the “don’t think of an elephant” principle and will only serve to give other unscrupulous employers ideas.

Especially the use of selfies as a means of employee control.

You've been hired by an algorithm and fired by a robot. https://t.co/7koal3BFoh

— Claus Hesseling (@the_claus) June 28, 2021

Amazon started requiring selfies in 2019 so that multiple people wouldn’t share a single account. The practice may help prevent people from using other accounts to steal packages. But there are other drivers who use the practice for more legitimate purposes, including to deliver more packages faster, which can bump up their ratings, or to fulfill deliveries without racking up parking tickets.

Flex drivers’ forums are littered with posts from people complaining that their accounts were terminated because their selfies did not “meet the requirements for the Amazon Flex program.” The photos appear to be verified by image recognition algorithms. People who have lost weight or shaved their beards or gotten a haircut have run into problems, as have drivers attempting to start a shift at night, when low lighting can result in a poor-quality selfie.

Drivers who believe they’ve been unfairly terminated have ten days to petition to have their accounts reinstated, but in that time, they cannot work any shifts. If a driver loses the appeal, they can ask for arbitration, though it costs them $200. For many drivers, who make between $18–$30 per hour delivering for Flex, it’s simply not worth it. For Amazon, though, botched terminations don’t seem to be tempering interest in the Flex program. In May alone, the Flex app was downloaded 200,000 times, according to SensorTower.

While there is reason to believe that the current labour market is shifting power towards workers, that partly depends upon worker literacy and awareness. In this case regarding how their prospective employer operates.

Just as we fear employers getting bad ideas from this story, perhaps workers/contractors will get wise and avoid such enterprises employing said algorithms?

Alternatively, in March we wrote about how many workers and contractors are now using tools to gather their own data to hold employer algorithms accountable?

Is the class war becoming a kind of data war where different apps will be used in an adversarial manner to protect either the employer’s or worker’s interests? Maybe.

Last summer we wrote about how more and more people have an algorithms as their boss. It’s not a new issue, even if the issues surrounding it are new to many people.

When Your Boss Is an Algorithm - For Uber drivers, the workplace can feel like a world of constant surveillance, automated manipulation and threats of “deactivation.” https://t.co/YXivuHHrFV

— Tactical Tech (@Info_Activism) January 2, 2019

DoorDash Is Proof of How Easy It Is to Exploit Workers When Their Boss Is an Algorithm https://t.co/K9pC2gNI9A

— Doug Bloch (@TeamsterDoug) July 29, 2019

Sorting through some merch in the airport on the way to "My Boss is Not An Algorithm" conference in Barcelona! Our struggle is international or it is nothing! ✊🏼✊🏿✊🏽🌎🌍🌏✊🏽✊🏿✊🏼 pic.twitter.com/3NUjTPzmwD

— IWW Couriers Network (@IWW_Couriers) April 24, 2019

Perhaps a subject for a future issue, and one we’ve touched upon in past ones, is whether influencers have algorithms as bosses since so much of their work is deducing, feeding, and serving the digital platforms.