Instead conspiracy fills the void of meaning

What does it all mean? That’s a question that the philosophically minded among us ask often. However I think even those who are not active philosophers, still dabble in the field, whether they realize it or not.

The primary means by which that question is answered, or contemplated, is via story, or narrative. Narrative is the gateway to philosophy, and stories are what make us who we are.

We touched upon this in a previous issue titled “Why stories make your future”, published six months ago tomorrow, that took a dive into the emerging field of narrative economics. Here’s the first paragraph from that issue:

Stories run the world. At least they help us make sense of it. They’re one of the primary means by which knowledge is transferred through time. We are who we are because of the stories we share.

One of the elements sorely missing from this current pandemic induced crisis are better stories. In our obsession with data, and our focus on numbers, we’re missing the larger role of narrative. Without narrative, we remain lost in the wilderness of confusion and chaos.

Humans are narrative based animals. We depend upon stories, and we will make them up if we don’t have enough to satisfy our needs.

In our current context, that’s where conspiracy theories come in. If we find ourselves dissatisfied with official explanations, we will seek out alternatives, or just make them up. Anything to fill the narrative void created by events we struggle to understand.

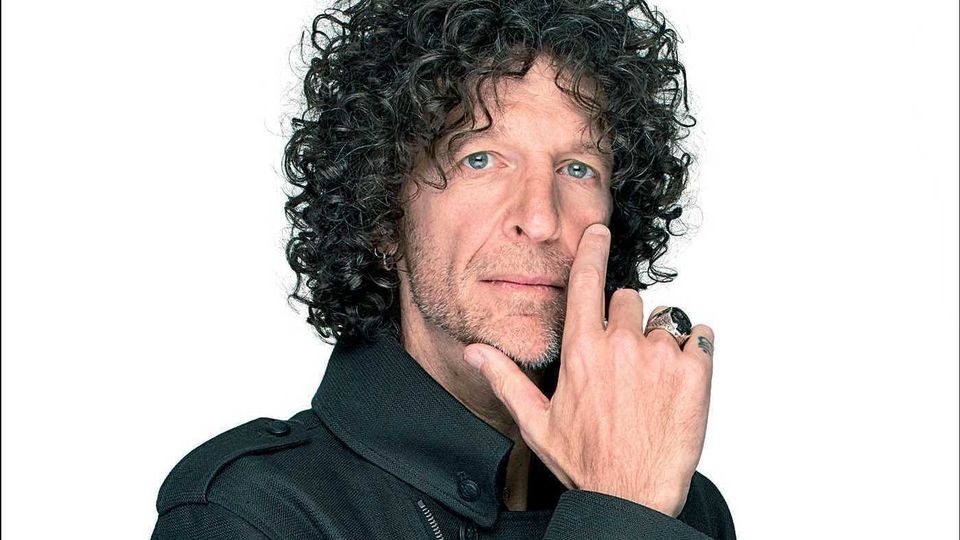

However I’m not one to blame the conspiracy theories, for the failings of public health officials. We touched upon this when wondering what would Howard Stern do if he were communicating on behalf of public health agencies. And last week we looked a bit at the subjective nature of health data, and how different people would interpret the same data differently (based on their subjective experience).

After a weekend of reflection, it struck me that what was missing were some good stories. By good I don’t mean “feel good” although I think that’s the by-product of a good story. I also don’t mean “good news”, rather I’d argue that a good story is an effective story. One that successfully transfers the knowledge embedded within the narrative.

The stories I feel that we’re missing, are the origins of this virus, the way it’s currently playing out, and our path forward, which hopefully involves better health outcomes and economic opportunities.

To some extent, I feel that this newsletter has been working to provide us with better narratives. I don’t claim this to be a primary focus, but rather a by-product of writing and researching everything else that is going on. However I’m definitely not satisfied with our current narratives, as they’re incomplete, and largely speculative.

Instead I wish that our public health officials were in a position or had the ability to tell better stories. Even if these stories were incomplete, or adapting to the available science, I think they’d have a far greater impact than the incoherence we’re currently being served.

Metaviews member Corvin Russell, who has been actively researching and writing about the pandemic since before it was officially declared, posted a sharp critique on FB today that I think sums up our current frustration with public health agencies and elected officials. While Corvin wrote this about Ontario, I think it applies to many other jurisdictions equally:

- They are slow to respond to science

- They are reluctant to issue clear and unambiguous directives, instead preferring to issue muddled and mixed 'suggestion' messages that allow people to default to convenience.

- They are not educating the public on how epidemics work and why directives are effective and need to be followed

- They have proceeded with the bias that laxity requires no evidence, while stringency and vigilance require definite evidence -- the exact opposite of the conclusion of every study of recent pandemic/outbreak management

- Still no mask requirements, only suggestions

- There is still no adequate test, trace, isolation capacity or planning, nor is there apparently any imminent plan for serious surveillance to determine infection prevalence.

- There is too much reliance on a patchwork of private actors 'doing the right thing' even though legislation allows for enforcement

- There appears to be no use of legislative tools to ensure adequate production of key elements in the medical supply chain for testing, PPE, and medicines. If the private sector is dawdling, government needs to mandate it or do the task itself.

A lot of these concerns that Corvin has articulated can be addressed via better narrative practices.

For example, if I were running a public health agency, I’d be making more of an effort to not just keep up with the emerging science, but more importantly popularize it, via stories and discussions. This is what Corvin does voluntarily with his social networks, but imagine how powerful and effective that would be if it was done at the agency level and publicly.

Similarly the point about people not understanding how epidemics work is crucial. In situations like this, public education is not optional, it is a requirement of success!?

While I don’t think that relying on people to “do the right thing” is an effective strategy, it too depends upon clear instructions and context, which is arguably only achieved by a solid narrative.

Parents understand the role of stories, and how stories are essential towards obtaining consent and trust from people, especially when you want them to do something they may not be inclined to do on their own.

All the children I’ve known went through a “why” phase, where they would ask that question incessantly. I always found the best way to deal with it was a story. Otherwise you just get a never ending supply of whys. A story helps take that why into the world of context and curiosity.

We’re currently seeing a never ending supply of whys. The lack of narrative in this crisis is understandably causing people to question public health advice and the crisis as a whole.

Unfortunately the virus doesn’t care. The virus remains ridiculously infectious and active. If anything we need better stories that communicate how this virus works, so that people might take it seriously. We’re still suffering from the false story that young people are not impacted, when they most certainly are.

David Fisman, an epidemiologist and professor at the University of Toronto has been a vocal critic of how this pandemic is being managed, and recently gave an interview with the provincial public broadcaster, TV Ontario.

“There’s something very, very wrong with how the folks running the provincial response to this epidemic are reacting to it and how they’re processing information.”

— Elamin Abdelmahmoud (@elamin88) May 25, 2020

Just utterly scathing evaluation of Ontario’s response. https://t.co/QDbnJ93dF0

Here’s a few excerpts that I think is relevant, in no small part because I feel he’s offering a narrative (of both the pandemic and its mismanagement):

But there doesn’t seem to be any clear strategic planning at the provincial level. We have lots of resources, good labs, and lots of smart people across the province. We have a province larger than France, but we have this dysfunctional messaging that’s treating Algoma the same way it’s treating Toronto the same way it’s treating Kingston. You have places that are hundreds of kilometres and sometimes thousands of kilometres apart, and the provincial hotspot is here in Toronto, and you’d never know it from the messaging coming out of the province, which treats the rest of the province as if it’s the GTA.

There’s something very, very wrong with how the folks running the provincial response to this epidemic are reacting to it and how they’re processing information. I think you see that in how long it takes them to catch up with the science. I’ve vented about this repeatedly — not that this is all about asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic spread — but the importance of that has been case closed for a number of weeks, and it seems like, only now, we are very gradually coming to the realization that people without symptoms might be transmitting this, and that might actually be important to epidemiology.

We’ve wasted weeks. You see that over and over again: with masks, with community spread. You see that now with testing. There are folks in individual health units who came up with mobile testing way back in February. You’re worried your test numbers have dropped? Well, you’ve just spent the last few months discouraging people from coming to test centres. If you want to get some situational awareness and to know how much infection there is out there, maybe you leverage some of these good ideas.

The lack of knowledge transfer and knowledge mobilization in this crisis is a symptom of narrative failure. We seem to take stories for granted, and forget who essential they are to our relationship with each other and the world.

It comes back to messaging, communication, and transparency. It’s having people buy in, having them understand that we’re on the same team and understand the stakes. I’d like to think the idiots in Trinity Bellwoods don’t want people to die as the result of their actions, but that’s what it is. If you spur disease transmission, you have a higher force of infection — you have more cases. Some fraction of those cases are going to find their target. They’re going to find that vulnerable person who goes into respiratory failure and dies or who gets a pulmonary embolism and dies. I’d like to think that most of those irresponsible people out there on the grass enjoying the sun aren’t bad or malicious people — they might be thoughtless — but there’s responsibility on the part of leaders to show people how to behave and to potentially sanction them if they’re messing things up for other people. You have to leave that up to the city and the province, but I think they should be. You’re hurting other people. It’s not fair.

The media obsession of the last 48 hours here in Ontario has been with a park in Toronto, Trinity Bellwoods, which saw a surge of people on Saturday, eager to catch some sun, sip some booze, and socialize. It seems fitting that this would become the big story, when there are few other quality stories in circulation.

As a story, the one about young people partying in the park epitomizes the divide between those who see this pandemic as serious, and those who regard it as a grand annoyance. Of course, it can be both, and if this particular story helps more people take this pandemic seriously, while also being annoyed, then that’s better than nothing.

However it doesn’t detract from our current narrative problem. We’re gonna need better stories if we have any hope of mitigating the worst elements of this pandemic, and the arguably worse impacts from the impending economic depression.

We touched upon this a bit in our latest AxisOfEasy salon:

What kind of stories have you found compelling amidst this pandemic? Are there stories about the pandemic that have helped you cope or get through it? What about stories that are inspiring, uplifting, or alleviate a sense of anxiety or uncertainty? Or what about stories that have entertained or distracted you as time passes?

Here’s one that Jeanette brought to my attention that we enjoyed and were inspired by: