Helping indigenous peoples affirm their Internet sovereignty and build their own networks

While the primary focus of the future fibre series is fibre optic based connectivity, our secondary focus is on the role broadband access plays in social and economic community development. Our hypothesis, which we’re finding overwhelming evidence to support, is that reliable and affordable high speed broadband connectivity is essential to the future prosperity and sustainability of rural and remote communities.

A great example of this, is MuralNet, an Oakland California based non-profit, that helps indigenous communities in the United States build their own high speed Internet networks. These are largely wireless networks, which while not as ideal as fibre, can often be deployed for far less money, and when installed effectively, can achieve significant speeds and reliability.

MuralNet is playing a key role in the move to connect indigenous communities to broadband networks. This is true on a policy level, and also on a practical level.

The #Havasupai Tribe, the most isolated Tribal Nation in the Continental US, recently got broadband access. In a few hours and for less than what a Toyota Corolla costs, #MuralNet helped Havasupai set up its own network.

— MuralNet (@MuralNetwork) December 4, 2019

Full story here --> https://t.co/9a64QGY9hR pic.twitter.com/TyHvRmGOlM

Nestled among turquoise blue waterfalls and cottonwood trees, the tiny Havasupai reservation is accessible only by foot, by mule or by helicopter. It's a five-minute flight from the rim of the Grand Canyon to Supai Village on the canyon floor, where 450 tribal members live in small homes made of panel siding and materials that can be easily hauled or lifted in.

It's no wonder Internet access has been a challenge. But recently, the Havasupai have had some help from the Oakland-based nonprofit MuralNet.

The help is a combination of technical knowledge - what equipment to buy, how to install and configure it. Yet it also includes knowledge of how to connect to an upstream provider, as well as regulatory hurdles that authorize the use of spectrum.

MuralNet helped the #Havasupai Tribe (the most isolated Tribal Nation in the Continental US) get access to the internet. A community member, Sally Balderrama, shared that having internet access helps her special needs son receive help via Skype. #NativeTwitter #DigitalDivide pic.twitter.com/kY3agM4uI7

— MuralNet (@MuralNetwork) December 20, 2019

Triggs trains the Havasupai how to install a network box outside a home. MuralNet — with the help of Flagstaff-based Niles Radio — built what's called a microwave hop from towers at the Grand Canyon's rim that beam a broadband signal down to Supai Village.

"And we were able to put up a network in just a few hours for less than the cost of a Toyota Corolla, frankly," Triggs says.

The total cost was closer to $127,000. Triggs says the isolated geography wasn't the issue. Rather, policy was holding up the process. The Federal Communications Commission finally granted the tribe a permanent broadband license last spring.

This is an element of micro or community ISPs that is not part of a fibre network.

Wireless spectrum is heavily regulated, and not in a way that benefits communities, but rather protects industry. The irony is that in many remote and rural communities, there’s no industry to speak of. And yet once that industry emerges, usually as a result of community groups or the local government, that’s when industry wants in.

Now the Havasupai want to increase the signal strength, but they've run into another hurdle. A second Internet provider, GovNET, says it may be interested in bringing broadband here. Now the FCC is dealing with concerns over competition while it is considering expanding the village's signal strength.

"We have the funds," Triggs says. "We have the money. We could do it. We could put materials that are needed in the towers and connect everything, but we have to wait for all this policy stuff again to sort out." Triggs worries that process could take years. "It just kills me because I feel like policy is actually causing the digital divide right now rather than helping to fix it."

Thankfully, due to both time, money, and considerable effort, they were able to obtain the license to expand their initial pilot project.

. @PCI_Initiative congratulates @MuralNet with successfully exercising access to the Education Broadband Service to achieve their objectives - the Havasupai Tribe secures a license to build-out their #community #broadband network https://t.co/224kxwV3KM

— People-Centered Internet (@PCI_Initiative) June 11, 2019

cc @vgcerf @meilinfung pic.twitter.com/LwemTg0JcZ

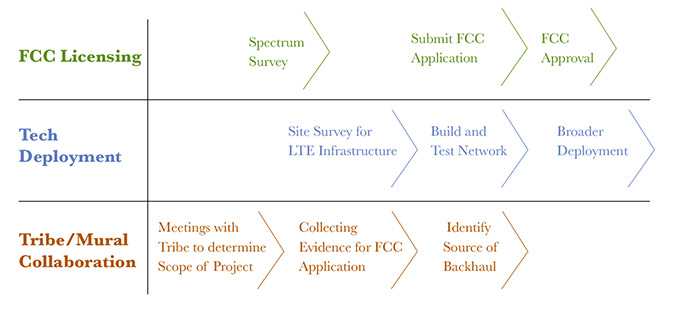

The method of building The Havasupai’s high speed Internet network is replicable. MuralNet had already assembled a kit using low-cost networking equipment that is then re-programmed with open-source software to operate and manage an LTE network. They consulted with Dr. Chad S. Hamill, Vice President for Native American Initiatives at Northern Arizona University, who was instrumental in assisting MuralNet in building key relationships with tribal communities, including the Havasupai. Councilwoman Ophelia Watahomigie-Corliss of The Havasupai Tribal Council vetted the partners, forged coalition amongst the Tribe and connected projects that could utilize Internet access immediately. Kelly Cullen of Niles Radio was already providing 30 mbps of backhaul for free to the Havasupai nation and enthusiastically volunteered his company’s time and expertise. The actual deployment of infrastructure took only a few people working half a day and $15k of equipment. The legal hurdles to spectrum, however, took a year and a half to overcome, requiring considerable time and legal fees.

Once again we see the role of free and open source software leveraging the availability of affordable hardware to enable smart and easy connectivity.

And once again we see that the government gets in the way of communities getting better connectivity, rather than the opposite.

The Havasupai’s fight for spectrum is not over. They have rights to use 20.5 MHz of non-contiguous bandwidth, allowing for their current educational programming. If they had access to all of the available 126.5 MHz of EBS spectrum, however, they could initiate telemedicine and tele-counseling services, emergency preparedness infrastructure, and economic development. They are not alone. About 2/3 of federally-recognized American Indian/Alaska Native and Hawaiian homelands have unclaimed EBS spectrum. The Federal Communications Commission is expected to change the rules regarding the licensing of EBS spectrum in the United States, which will most likely end with auctions that privilege large commercial interests. Market forces have not bridged the rural digital divide on a massive scale but community networks are making a dent. Native nations should have first priority in claiming this spectrum over their lands. If the FCC grants this, they will be ready to deploy their own networks in order to meet their people’s needs in ways that match their values, their vision of the future, and their way of life.

While skepticism should remain the default position, the FCC, under pressure from organizations like MuralNet, are showing signs they will take action to help improve the connectivity of these indigenous communities.

Want to know our origin story? Thanks @stanfordmag for sharing! #digitaldivide #urbanruraltribal #tribalprioritywindow https://t.co/rORr4sd4uF

— MuralNet (@MuralNetwork) February 19, 2020

“I’ve been talking to the chief of staff of the FCC’s wireless telecommunications bureau more often than my own mother,” Triggs says. “This is where being a little sister has been really helpful—I know how to needle people.” Last year, after months of consultations, the FCC announced the creation of a priority window, from February 3 to August 3, 2020, during which federally recognized American Indian tribes and Alaska Native villages can obtain unassigned EBS spectrum over their lands. In August, the remaining EBS spectrum will go up for auction.

How can a spectrum license help your tribe? A license gives your tribe control over your land's airwaves. MuralNet offers FREE information and help with applications, learn more: https://t.co/c5nZcOAzY1 #NativeTwitter pic.twitter.com/nfCQY4eSC2

— MuralNet (@MuralNetwork) December 9, 2019

Triggs describes the spectrum to tribal leaders as “invisible rivers in the sky.” She has made it her mission to ensure that people on all 514 tribal lands and Native villages with unclaimed EBS spectrum know about the opportunity to apply for it. She and a panoply of partners are hosting regional meetings and visiting tribal councils across the country to spread the word. “There will be a representative for every tribal land who knows what the opportunity means,” Triggs vows. “Whether they can get through the politics, I can’t say.”

Flying into Juneau to do spectrum acquisition outreach hosted by the Central Council of the Tlingit & Haida of Alaska. Thank you! #2.5ghz #tribalprioritywindow pic.twitter.com/sG3ZP5ruHN

— MuralNet (@MuralNetwork) March 2, 2020

Here’s a podcast with Mariel and the lawyer who helps MuralNet with regulatory affairs:

The FCC just opened the Tribal Priority Window for 2.5 GHz spectrum - this is a great opportunity for expanding broadband in Indian Country - great discussion with Mariel and Edyael at MuralNet. https://t.co/VvtF031m5d

— Christopher Mitchell (@communitynets) February 4, 2020

While it is encouraging that these policies are designed to help rural indigenous communities, they may not actually achieve their desired effect. For many, this priority window is unrealistic, as the bureaucratic hurdles and literacy required to apply can be far too onerous for most.

Window Opens For Tribes To Seek Federal Licenses For Rural Broadband Access #pacnw #feedly https://t.co/aLO1mfM2Du pic.twitter.com/MD1UN3AxBP

— NWFogCutter (@NWFogCutter) February 17, 2020

One of the issues is basic eligibility. From the article linked above:

One of the largest organizations representing tribes, the National Congress of American Indians, is asking the FCC to reconsider eligibility requirements, particularly when it comes to the definition of tribal land and the inclusion of “rural.” The organization said tribes that don’t have reservations or that don’t have contiguous parcels of trust land would be left out.

The FCC defined rural tribal lands as being outside urbanized areas and with a population of less than 50,000 people. The National Congress of American Indians said that could exclude tribes with land near Seattle or Phoenix, for example.

However it’s not just about eligibility, but the amount of work to apply in the first place:

👋A quick thread: I'm one of three women working together via @MuralNetwork to complete an application for federal funding to build out a Tribally-owned broadband network. Additionally, we're working on a blog to document the application process. Why?

— Cat Blake (@cat_hannah_b) March 3, 2020

The first post is below, where I talk about how the sheer amount of resources needed to complete an application is an automatic barrier to entry. If we want these programs to be vehicles for empowerment, they need to be accessible. https://t.co/37l4uGFRlN

— Cat Blake (@cat_hannah_b) March 3, 2020

Part of what’s going on is that these programs often favor big, incumbent Internet Service Providers in their design, and create significant hoops and hurdles for the small, locally-driven solutions that are often the only way forward for Tribal communities. These hoops and hurdles are nuanced, and we hope to explore several different angles to this issue throughout this blog. But I’ll start here with one that seems to run through the heart of the problem: lack of resources.

Federal grant and loan applications are not easy. The application guide for the Department of Agriculture’s ReConnect program is 238 pages of terms and conditions, eligibility requirements (for applicants, for projects, for service areas), federal requirements, financial history documentation, licenses and agreements, and much more. Applications have to include a legal opinion, analysis from a professional engineer, years of financial audits, network designs, business plans and revenues, and competitive analysis of the market, just to list a small sample. Applicants are required to provide information held to a higher standard of granularity than we ask the Federal Communications Commission to provide to the American people, such as a premise-level description of entities served by a network and an account of specific competitors and their service tiers in a specific community.

There needs to be a streamlined version that makes it easier for communities to comply with the general expectations of funding agencies using available expertise and resources. Otherwise such policies become pointless if the people they’re meant to benefit are not able to apply in the first place.

This level and sheer amount of information is not, however, a reasonable task for three people with outside jobs to tackle together as a part-time project. That’s the situation we’re in, and the situation that many other Tribal communities face when they decide to pursue funding opportunities. My two co-conspirators on this endeavor are incredibly smart, talented women, they’re broadband policy experts, one is even a grant-writer. And this process is really, really hard. It’s clear that it’s the very communities who could benefit from these programs most — Tribal communities that have rallied to look for a way to build their own networks after decades of being bypassed by private providers again and again — that are being de facto excluded from participating.

Finally, this is an article written by Mariel Triggs that details the process MuralNet engaged in to connect the Havasupai Tripe, including this relevant graphic of the process timeline:

Her conclusion sums up the challenges moving forward:

By far the most time-consuming and expensive hurdle in bringing high-speed Internet to homes in Supai was obtaining permission from the government to use spectrum for LTE broadcasting. While it is fortunate that the FCC had the foresight 30 years ago to reserve bandwidth for educational use, it is underutilized, and the rules for its use are outdated. Open licensing has not happened since 1995. The FCC rule changes of how licences for the 2.5 GHz Band are granted are timely. Now the FCC is considering giving current licence holders, local tribes, and local educational institutions priority for claiming unlicensed 2.5 GHz spectrum and then auctioning off the remaining spectrum rights. But, there is also the possibility that the FCC will not offer priority licencing windows and instead just go straight to auction. If these priority windows are not implemented, tribes and schools will be hard-pressed to compete with the major telecoms who are unlikely to develop broadband on tribal lands due to predicted low return on investment. This would be disastrous for the tribes.

If tribes can obtain FCC licenses for spectrum on their own lands, then they will be able to self-deploy LTE networks just like the Havasupai’s and provide high-speed Internet access to their people. Policy makers determine the rules, but these rules can either empower tribes to provide the much-needed broadband access for their communities or prevent tribes from doing so. Chairwoman Coochwytewa states that “without a permanent licence, we are worried that the Tribe might lose our EBS spectrum, which would be a terrible blow to the progress that we have made so far. I do not want to see our people’s progress halted by a regulatory hurdle.” Hopefully, policy makers will see that tribes can succeed – and already have succeeded on their own – and already have succeeded on their own and will give them a chance at self-determination in the Internet Age.

We’ll keep an eye on this issue, and circle back once this priority window has closed, or if it is altered. Under the current configuration it is doubtful that the policy will be successful, as many tribal communities will not be able to apply in time or under the current criteria.

While wireless is sensible in many remote and rural communities, the regulatory hassle is a strong deterrent. Fibre is a desirable end, but it can be expensive, and the expertise is not as freely available as is the case with wireless technology. Hopefully that will change over time.

A few years ago I was able to visit Attawapiskat, as they were just getting connected to fibre via the Western James Bay Telecom Network, which is owned by the native communities on the west coast of James Bay. Perhaps we’ll do a future issue on their efforts, as they’ve recently started moving towards full fibre to the home.

Western James Bay Telecom Network to upgrade internet service for 3 communities https://t.co/ikC27Y5Atd

— Wawatay News (@wawataynews) January 31, 2019

“Future Fibre” is a recurring series in the Metaviews newsletter where we share some of the research, other models, news, and ideas around community based connectivity.

The series is sponsored by our friends at EasyDNS:

I’ve been an EasyDNS customer for almost 20 years (and I know a number of you are as well based on my recommendation). Mark Jeftovic the co-founder and CEO is a long time friend and Metaviews subscriber. EasyDNS is one of the best service providers on the Internet, and Mark ensures his customers have the benefits of the latest and most secure technology.

Mark also writes a smart newsletter called #AxisofEasy and has just published a fascinating book called “Unassailable”, which we recently reviewed. I’m thrilled that Mark shares my belief in the potential for micro-ISPs and is sponsoring this series as a result.

And here’s the bonus video for this issue, a spectrum sovereignty workshop by Mariel Triggs: