A reminder of why wireless is substandard

While the pandemic has helped reinforce the essential role of the Internet in our lives, it has tragically not increased our understanding of how the Internet works, nor our literacy about to use it effectively.

Part of the proof of this sad state is the golden era of conspiracy and disinformation that saturates our social media and information ecosystem. However a deeper and more disturbing sign is our dysfunctional and delusional approach to Internet access and connectivity.

As part of our ongoing Future Fibre series, we’ve been learning about communities around the world who have dramatically improved their economic and social opportunities by taking control of their Internet connectivity. As part of this research we’ve learned a range of insights and best practices that help us understand what can be done to not only fix what is broken but plan for long term success.

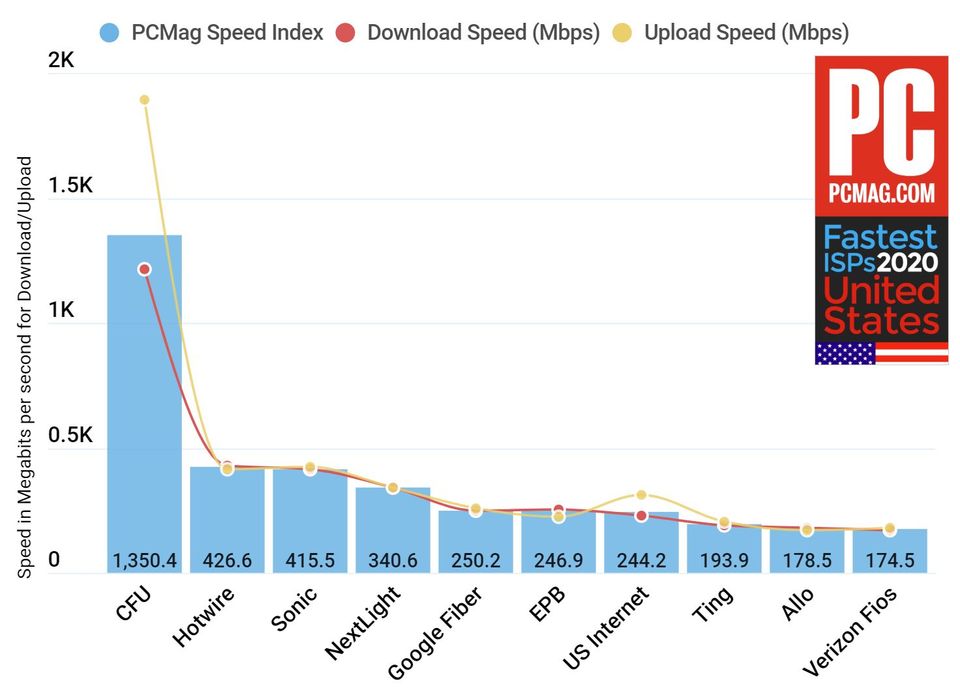

One of the most important insights or lessons is the necessity of fibre optic connectivity rather than wireless. While this remains true in any community, it is particularly essential in rural and remote communities that are already suffering from expensive, slow, and unreliable access.

Unfortunately wireless remains the primary solution chosen by politicians and uninformed residents due to the false belief that it is cheaper and easier to deploy. The problem with this approach is that it will ensure that rural residents remain second class (at best) and left behind in an Internet ghetto of slow speeds and apps that won’t work.

Wireless will not be able to keep up with the evolution of the Internet as the speeds available over the air will not scale as fast as the speeds available via fibre optic connections.

Given that most urban users and smart rural users will have fibre connections, their experience and use of the Internet will advance at an exponential rate compared to uses stuck on wireless. Developers, companies, and governments will design applications and services for these users, taking advantage of available speeds and capacity.

Wireless users meanwhile will be left in the dustbin of history. This is true both of terrestrial wireless users and those seeking high speed via low earth orbit satellite, as offered by SpaceX’s Starlink service. They cannot and will not be able to keep up with speed increases that will be possible on existing fibre optic connections.

For example, check out this latest research from the UK:

London scientists build 'ultra broadband nearly three million times faster' than UK home fibre optic internet connections https://t.co/G7We8alb0h

— Evening Standard (@EveningStandard) August 16, 2020

A University College London-led team used amplifiers to enhance the way light carries digital data through fibre-optic broadband to achieve a record 178 terabits per second - almost three million times faster than the average UK home connection.

The new record was achieved by transmitting data in a greater range of colours than is typically used in optical fibre in order to increase the bandwidth.

While it is amusing that these speeds were accomplished by using more “colour” it also illustrates how much potential can still be wrung from fibre optic technology. The article also mentions similar research underway in Australia:

In May, a team in Australia used a single “micro-comb” optical chip containing hundreds of lasers to transfer data across existing networks in Melbourne at a speed of 44.2 terabits per second.

It is with this future capacity in mind that many communities are investing in fibre optic infrastructure, either publicly owned or cooperatively owned:

The co-ops that electrified Depression-era farms are now building rural internet, feat. @communitynets: https://t.co/GoQ0vGg2LD

— Muni Networks (@MuniNetworks) August 5, 2020

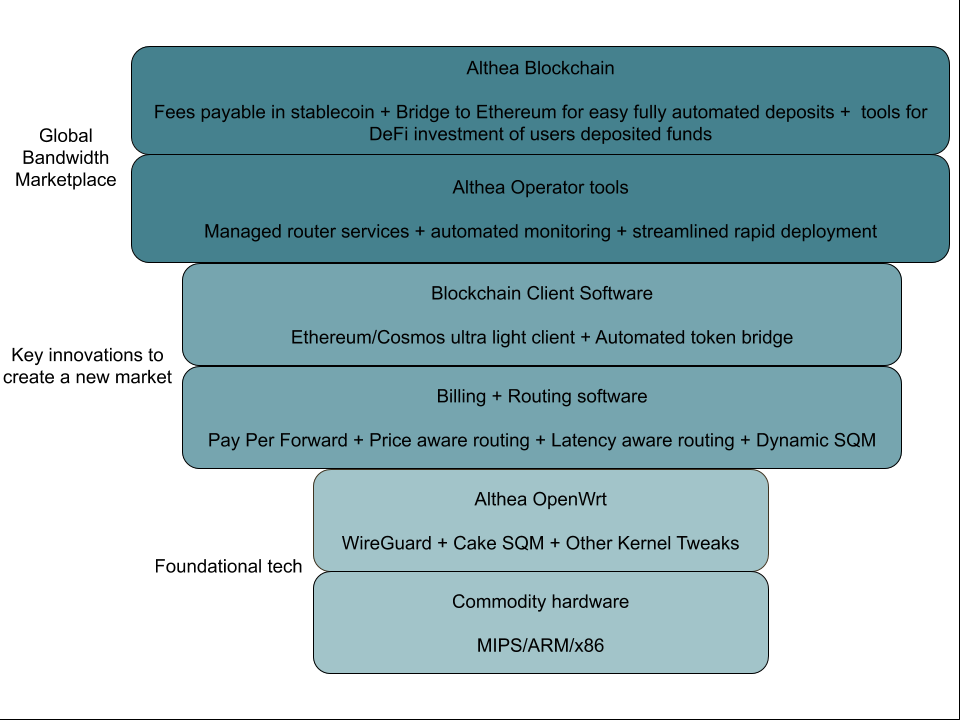

Across the rural US, more than 100 cooperatives, first launched to provide electric and telephone services as far back as the 1930s, are now laying miles of fiber optic cable to connect their members to high speed internet. Many started building their own networks after failing to convince established internet service providers to cover their communities.

This is of course a recurring theme in our Future Fibre series, as we profile different communities that are engaged in this kind of infrastructure and investment.

Articles like the one above are increasing, as communities scramble in response to the pandemic to upgrade their infrastructure. Sometimes it’s a co-op, other times it is a P3: public private partnership:

A Mississippi-based technology company plans to install more than 33 miles of underground fiber infrastructure that will help offer ultra-fast broadband internet access to rural areas by the end of the year.https://t.co/A9z71rHejX

— WJTV 12 News (@WJTV) August 17, 2020

It is interesting to see this seismic shift in the way we prioritize Internet connectivity, and in particular towards the recognition that fibre optic connections are not just a short term fix but a long term investment.

In Italy, where the pandemic hit early and hard, there’s now talk about building a national fibre optic infrastructure that would be shared and overseen by the state:

Italy's economy ministry wants independent ultra-fast broadband network, says source https://t.co/35uhZPjAnX pic.twitter.com/fc07yBXp7b

— Reuters (@Reuters) August 23, 2020

Italy’s economy ministry wants a single, independent ultra-fast broadband network that is independent of former phone monopoly Telecom Italia, granting equal access to all market players, a treasury source said on Sunday.

The state would keep a strong role in the new company, the source added.

The Italian government is trying to negotiate a deal between Telecom Italia (TIM) and Open Fiber, which is jointly owned by state lender CDP and utility Enel, to merge assets and create a single national champion. But TIM is reluctant to accept less than 50% of any network.

While communities and countries focus on investing in Internet infrastructure, it will be interesting to watch whether this (seemingly nonexistent) debate between fibre optic and wireless will develop further.

I do wonder if the urban experience is partly responsible for the lack of debate, as urban density means that both fibre and wireless co-exist. Whereas in rural and remote communities, there’s usually pressure to choose one over the other out of a need to limit cost and maximize investment.

The danger of this bias is that it means wireless is regarded as a viable option when it clearly is not.

Hopefully people clue in to this now, before they find out, in a few years, that the Internet has moved on, and that their wireless connection is hopelessly out of date.

Finally, if you’re wondering how exactly fibre optic cables work, here’s a decent explainer: