Enabling a competitive open connectivity market

As our Future Fibre series has progressed, so to has our understanding of what is possible and what ought to be. It’s not that the grass is greener elsewhere, but when you learn of the cheap, fast, and reliable Internet that other communities posses, envy is a reasonable response.

A key insight or lesson from our research so far, is that municipal involvement is not only essential, but often provides a direct correlation with the quality and cost of Internet connectivity. The more involved a municipality gets, the better the situation overall, with direct and positive impact on both economic development and social well being.

Which is why the story of Ammon Idaho is interesting and relevant. We learned about them via a recent report from our friends at the Open Tech Institute:

Our 2020 #CostofConnectivity report by @chao_becky & @clerppark analyzes 760 internet plans across 28 cities worldwide and finds substantial evidence of a broadband affordability crisis in the United States.https://t.co/AP01AO8Gtb pic.twitter.com/78cm51yocJ

— Open Tech Institute (@OTI) July 15, 2020

In our most extensive Cost of Connectivity report to date, we find further evidence that consumers in the United States pay more on average for monthly internet service than consumers abroad—especially for higher speed tiers. This year’s report examines 760 plans in 28 cities across Asia, Europe, and North America, with an emphasis on the United States. Our latest research on internet affordability is especially timely as millions of people have moved to online classrooms, telework, and telehealth during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Access to the internet is far from equal, and the digital divide disproportionately affects Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) communities and low-income households. We’ve long known that cost is one of the biggest barriers to internet adoption, and it is likely to become an even bigger barrier as jobs and incomes are lost during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This is a fantastic report as part of a larger study conducted by OTI. While it has a range of findings and recommendations, I found it notable that a relatively small suburb in Idaho would rank in the top ten of lowest average prices. This is also highlighted in the context of affordability:

We find substantial evidence of an affordability crisis in the United States. Based on our dataset, the most affordable average monthly prices are in Asian and European cities. Just three U.S. cities rank in the top half of cities when sorted by average monthly costs. The most affordable U.S. city—Ammon, Idaho—ranks seventh. The overwhelming majority of the U.S. cities in our dataset rank in the bottom half for average monthly costs. Internet policy scholar Jonathan Sallet recommends that $10 per month is an affordable benchmark for low-income households. Only six plans in our U.S. dataset meet this $10 benchmark at any speed tier (only four meet Sallet’s 50/50 Mbps recommendation), and all six are offered in Ammon. Out of 290 plans in our U.S. dataset, 118 have advertised initial promotional prices of $50 and under—and only 64 of these plans advertise speeds that meet the current FCC minimum definition for broadband. In addition, some ISPs have abandoned low-income neighborhoods in a form of “digital redlining.” Moreover, COVID-19 has exacerbated a longstanding digital divide that disproportionately affects low-income households and Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) communities. As jobs and incomes are lost, this affordability crisis is poised to worsen. Congress and the FCC must take immediate action to stop digital redlining and help more people get online.

The folks at OTI were so impressed with what’s happening in Ammon, they published a separate case study to highlight the municipality’s success:

The Cost of Connectivity in Ammon, Idaho https://t.co/sExvt13dm3 via @newamerica

— Mayor Sean Coletti (@AmmonMayor) January 22, 2020

In the late 2000’s, the Ammon City Council in Idaho recognized that private broadband providers alone were not meeting the city’s needs. In response, the city created its own fiber optic network, which now serves the government, businesses, and residents, transforming Ammon into one of the most affordable broadband markets in the country. Across the city, customers are logging into high-speed gigabit connections with advertised prices as low as $9.99/month—faster and cheaper than plans available to many of their neighbors in Idaho and around the country. The Ammon open access network demonstrates that local partnerships between an active municipal government and internet service providers can be successful in providing residents with affordable and reliable high-speed internet.

While I’m skeptical about this gigabit connection for $10/month, it remains a compelling and symbolic price point. Imagine if Internet was neither a significant monthly cost, nor congested due to low speeds and poor connection quality. This is what’s possible when the infrastructure is owned by the public, and the market is configured towards healthy competition.

Ammon is also an interesting story, as it does not involve any grand vision or charismatic champion, but rather common sense, as one might associate with somewhere like Idaho.

The municipality’s journey towards fibre infrastructure started with basic organizational needs. The local government wanted their internal connectivity usage to be more efficient and cost effective, and in 2008 decided it would be cheaper, both in the outset, and in the long term, to build their own fibre network.

They didn’t start out with the idea of connecting everyone, and between 2011 and 2016 the construction of the network primarily focused on government buildings, and schools. However as businesses expressed interest in connecting, and paid money for the construction and installation, the idea of expanding the network took root.

Starting in 2016 the municipality started connecting residential neighbourhoods, with home owners given the option of a roughly U$3,000 install fee, which could be paid up front, or amortized over 20 years as a special assessment tax on their property. Although this 20 year payment option is only available for people when the construction is done in a particular neighbourhood. If they opt-in later, they have to pay the fee up front.

The municipality runs this network for the benefit of the community, as a non-profit, that enables companies to offer internet connectivity via the infrastructure.

What’s particularly interesting about this kind of set up, is that it disconnects the infrastructure from the provider. As the video above mentions, with most providers, the speed they advertise is inevitably different from the speed you get. However when the infrastructure is a public utility controlled by the municipal government, they can control and verify the speeds, mandating that providers are honest and transparent about the services they provide using that infrastructure.

Residents of Ammon, Idaho, enjoy 1Gbps fibre to the premises broadband for $9.99 a month, with no contract and a choice of 8 service providers. Impressive. https://t.co/wbGXkPA4LK

— Stuart Lambert (@qology) October 22, 2019

This arrangement that treats infrastructure and services as distinct, would be foreign to most telecom users. Part of the con of telecom is to shroud the technology and services in jargon and mystique so that people don’t understand how it works.

Yet at a fundamental level, telecom is really quite straightforward. Internet connectivity in particular. It’s really just as a network diagram conveys, a matter of branching on to an upstream provider who connects to other providers who connect to the Internet at large.

Therefore if you have public infrastructure, you can then allow private companies to deliver a range of services on top of it, that connect you to the world.

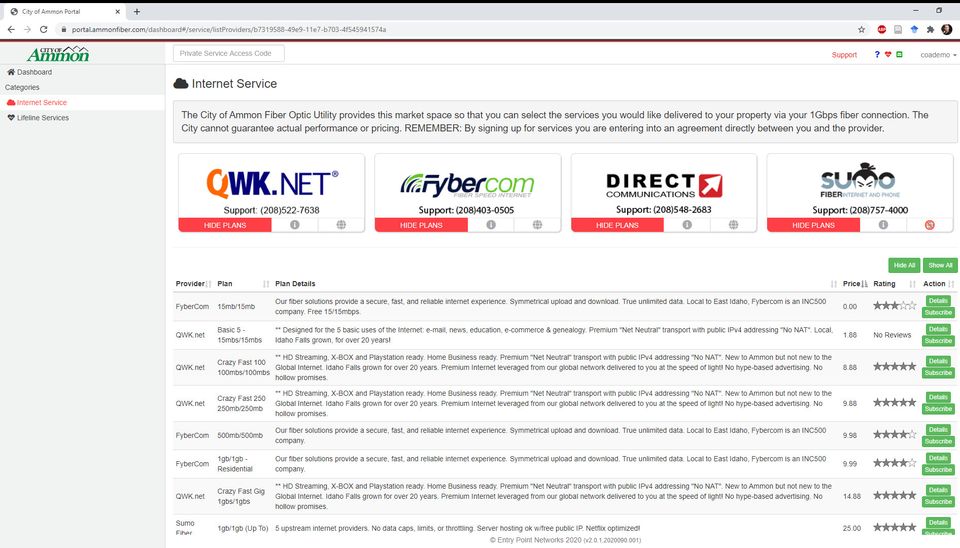

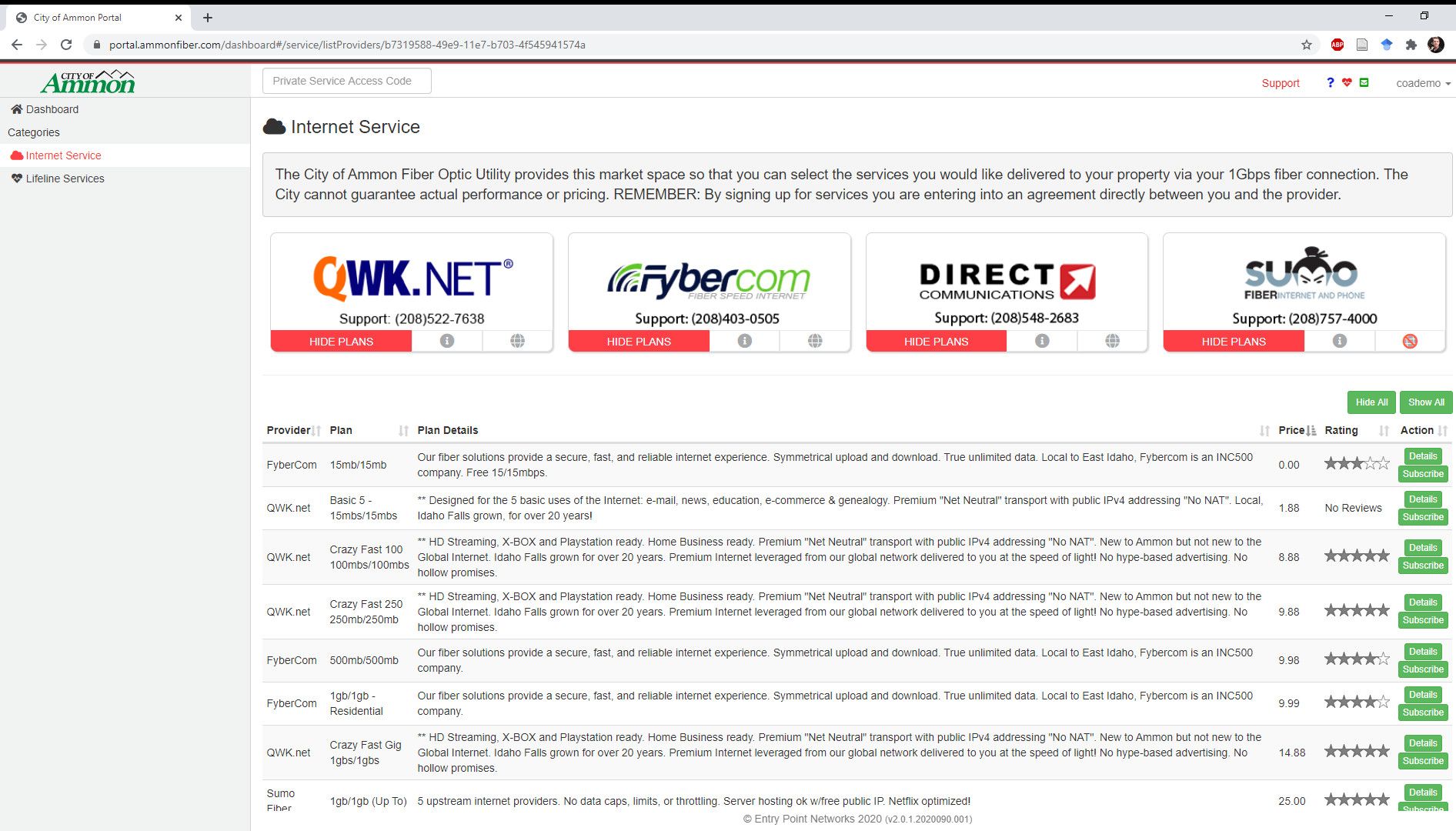

To get a glimpse of how this works, you can see all of the internet plans Ammon offers by going to their website, clicking on My Account, and logging in with the dummy credentials ‘coademo’ for both the username and password.

It will then show you a range of plans that prospective clients can sign up for.

This is an impressive list, even if it is only derived from four different companies. It’s also worth repeating, that this is for a community of roughly 17,000 people. Imagine something like this for a city like Toronto or NYC?!

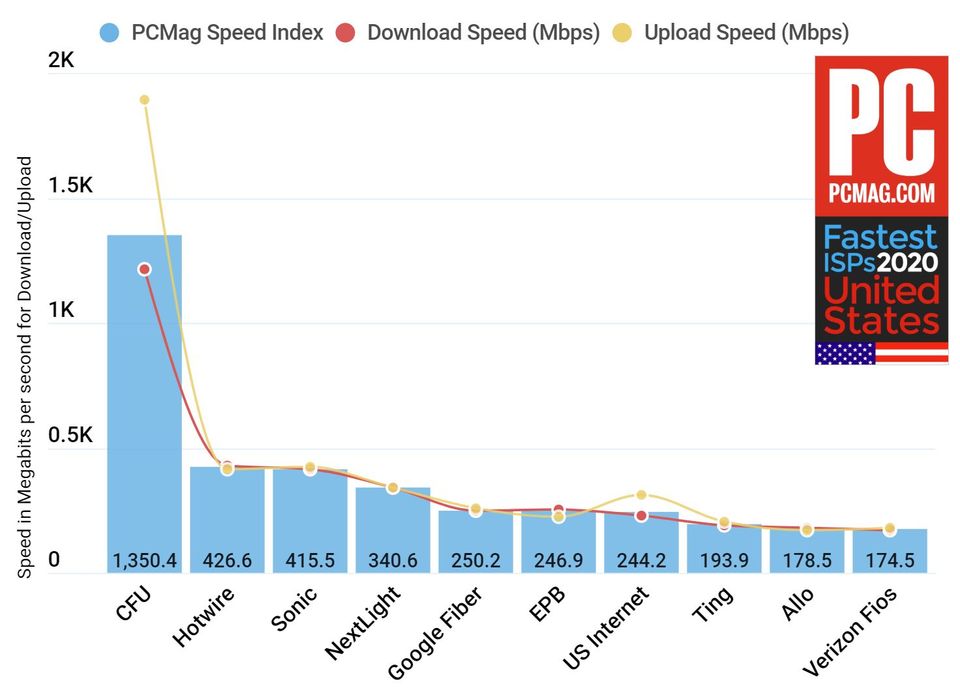

While a genuinely competitive market in a smaller community is remarkable, it would be revolutionary when scaled up to a larger city or megalopolis. In many cases this is why countries in Asia and Europe have radically lower prices for telecom services. They have far higher rates of competition.

The Ammon experience is incredibly helpful and informative, as it shows not only the role municipalities should play when it comes to enabling better connectivity, but more importantly the crucial role they can and should play when it comes to governing and regulating a competitive marketplace.

Ironically a marketplace enabled by a government owned monopoly/utility. Demonstrating that it’s rarely either/or, but an appropriate combination and configuration of both.