Will robots help secure our food supply?

The potential for automation and technology in agriculture is significant. Similarly this pandemic has increased awareness and interest in our food supply, which will fuel the desire to understand and trace where our food comes from.

Certainly it is the latter that draws me in. I think there’s tremendous value in understanding both where our food comes from, and why. Public education around agriculture is essential and important. Partly to inform and empower consumers of food to influence agricultural practices, but also to encourage more consumers to consider becoming producers.

On a small scale, this is part of the appeal or potential of agricultural technology. It could enable wide spread decentralized production. However on a large scale, agricultural technology, and in particular automation, has an important role to play in expanding production while also encouraging more sustainable and responsible practices.

In today’s issue we’re going to focus on the latter, and the role that robotics is starting to play on large scale farming operations.

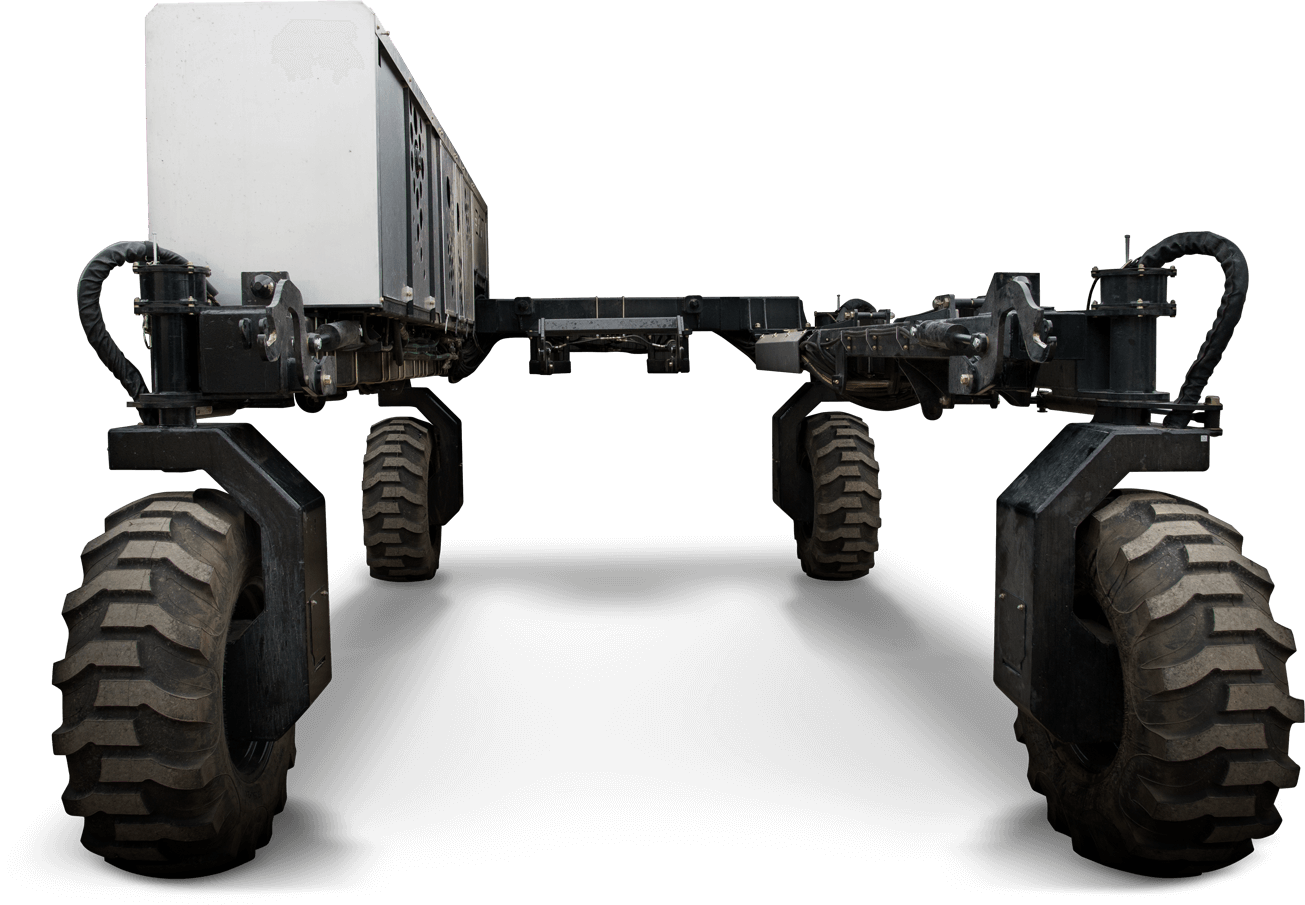

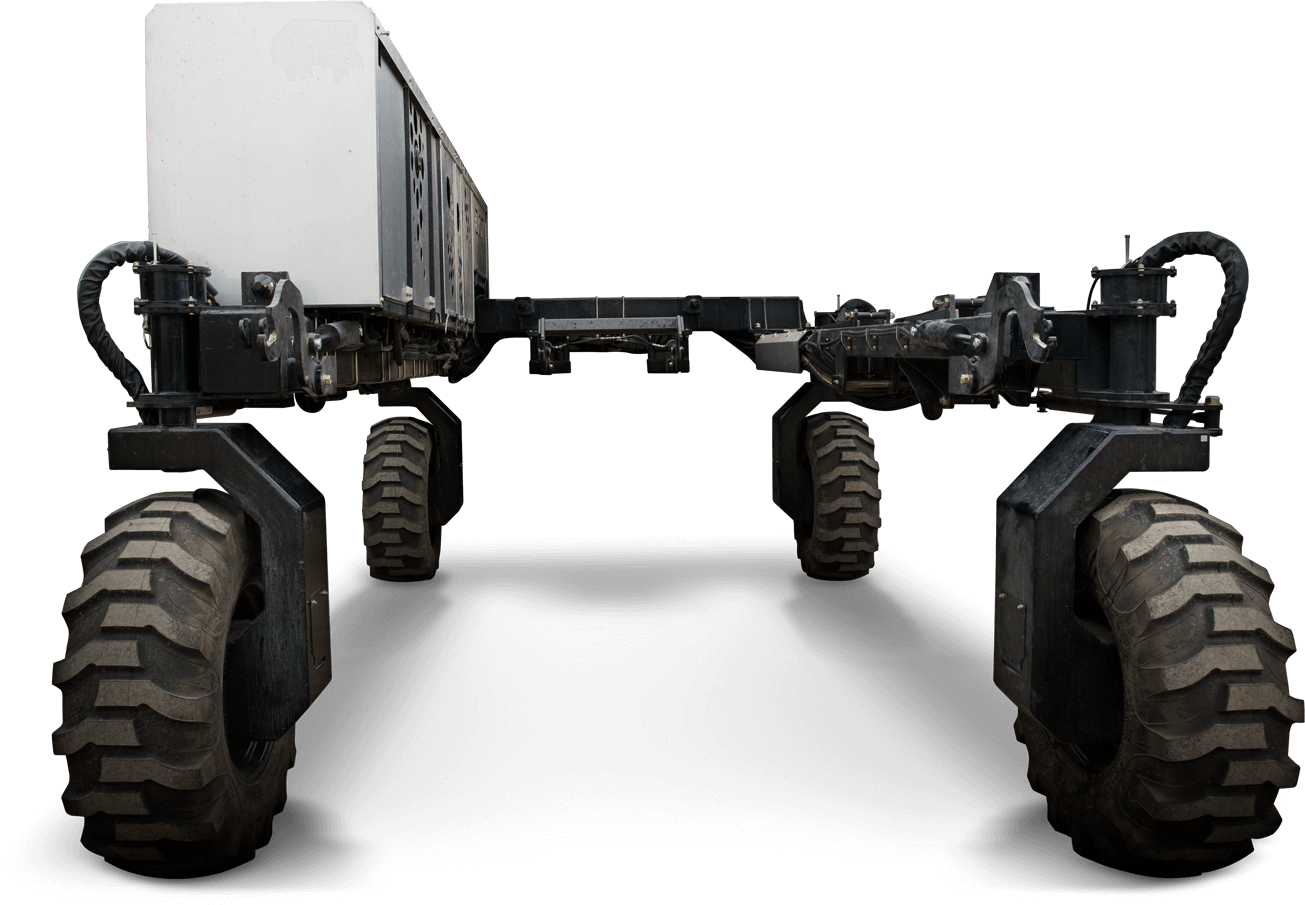

Dot is a mobile diesel-powered platform designed to be a versatile autonomous vehicle for a wide range of agricultural applications. (Although while it is initially focused on agriculture, it will no doubt be ported to other industries where heavy equipment is employed). While it can and often is compared to an automated tractor, the analogy is not entirely fitting, in so far as a tractor is not generally compared with work horses. The linage is there, but the upgrade is considerable.

Unlike a tractor or a horse, there’s no riding a Dot. It’s meant to be controlled remotely, or more accurately programmed by the farmer. Using software that runs off a (Windows) tablet, the machine is programmed via a relatively friendly interface, that allows the farmer to set a route across a field, and instruct the machine what to do. This might include tilling, planting seeds, spraying fertilizer, or a range of other applications.

Dot is a tractor replacement, but not yet a combine replacement (combines literally combine a range of functions to harvest crops). However it is designed to accompany a combine, by helping to offload and transport whatever has been harvested.

The machine is outfitted with a wide range of sensors, and imaging, that not only enable it to do the task programmed, but also gather data about the field and the crops, enabling an emerging kind of precision agriculture that uses just the right amount of resources. The producers of Dot claim that the machine will save at least 20% of fuel from being lighter than other machines, and similar savings of resources and materials from practicing precision agriculture.

Dot was developed in Regina, Saskatchewan, by Seedmaster farm equipment, and launched in 2017. Over the past three years they’ve been engaged in a wide range of testing, but the machine was largely designed for the large agricultural operations that exist in the great plains of North America, i.e. the Canadian Western Prairies and American Mid-West. The company estimates that a single Dot machine can work roughly 2,000 to 3,500 acres.

Last year I was part of a series of events put on by Farm Credit Canada. This provided me with the opportunity to meet a diverse range of farmers, who had agricultural operations ranging from a few acres (an intensive organic farm in the lower mainland of British Columbia) to those farming tens of thousands of acres. Dot is clearly designed for the latter rather than the former.

Similarly agricultural operations faced a serious labour shortage before this pandemic, and that has only been exacerbated by travel restrictions, even if foreign agricultural workers are still permitted in the country.

Let’s take a moment here to interrupt our normal programming and recognize the dire situation many migrant farm workers are facing:

The outbreak at the industrial greenhouse near Chatham, Ontario was declared April 27 and still grows. Justice for Migrant Workers @J4MW reports 100+ are sick.https://t.co/AQtuXro8F3#canlab #onpoli #cdnpoli #covidcanada

— Rankandfile.ca (@rankandfileca) May 17, 2020

And to be clear, I’m not suggesting that we should replace these workers with robots. Rather I’m suggesting that the labour shortage is being used as an excuse to treat humans poorly, and that perhaps the appropriate solution is to balance out the needs of workers with the abilities offered by automation.

However the problem with systems like Dot is scale. While the machine may be designed for large scale farming, it would take a lot to actually scale Dot up so that it is produced and manufactured at the scale the agricultural market merits.

After all the agricultural industry is dominated by big business. There are only a handful of equipment manufacturers, and the vast majority of farms exist because the current operators inherited the company (a/k/a land and equipment) from their family. The sector may have one of the highest barriers to entry, as the amount of capital, land, equipment, and knowledge necessary is considerable.

It should come as no surprise that in order for Dot to scale, they had to find a larger company to partner with, and then be bought by, if they have any hope of seeing their technology manufactured and deployed widely.

I had been following Dot and their company, DOT, for a while, and this recent purchase motivated me to write this issue, so we could document this transition.

Raven to Acquire Full Ownership of DOT® https://t.co/Vff5ZsoaDq

— Scott A. Shearer (@ScottShearer95) March 31, 2020

Fusing DOT, and the recently acquired Smart Ag® autonomous perception and path planning technology, with our core technology platforms in guidance, steering, and machine control enables Raven to deliver revolutionary autonomous solutions and greatly accelerate our long-term growth in Applied Technology. The company is currently moving forward with commercialization of Raven Autonomy™ and will be expanding its portfolio with new offerings, which will increase the value of autonomy to end-users at a rapid pace.

“We see tremendous synergies between our current business and in the investments we have made in DOT and Smart Ag, an Iowa-based autonomy company which we acquired last November,” said Wade Robey, Executive Director of Raven Autonomy. “We are very excited to be a leader in ag autonomy, and we are committed to working with our customers and partners to help bring these exciting new technologies to ag markets around the globe. Developing solutions for ag autonomy expands the total addressable market served by the Applied Technology Division by several billion dollars and positions the business for tremendous growth over the next several years.”

Corporate speak tends to cause my eyes to glaze over, and agricultural corporate speak is a particularly incoherent dialect. With that said, the two paragraphs above are not that bad. They provide a glimpse as to where Raven wants to go with this technology.

Perhaps their primary, and larger competition, is John Deere. The heavy equipment manufacturer now refer to themselves as a technology company, and have been aggressively adding automation to their higher end tractors and combines.

Similarly the data being generated by agricultural operations is incredibly valuable, as it helps inform not only what is grown, but how it is grown, and with what tools or products. We touched upon this in our post on Farmers as Hackers.

The problem of course with the farmer as hacker is that the individual or small company can’t survive in a sector dominated by giants.

Raven buys DOT with plans for expansion https://t.co/rwnyYhOg6b

— Grant Merron (@GrantMerron) April 13, 2020

“As a family, we couldn’t take on putting DOT where it needed to be by ourselves,” said the founder and owner of SeedMaster farm equipment near Regina.

DOT Technology Corp. builds an autonomous platform that can be fitted with several, interchangeable implements.

After five years of development and last season’s initial commercial releases of DOT, Beaujot partnered with South Dakota’s Raven Industries, which had been providing the guidance technology for the unit.

Raven Industries is not only able to provide capital and scale, but also add other technology to enable full autonomy:

Smart Ag developed technology around perception, obstacle identification and classification, as well as obstacle avoidance that is critical for autonomous farm equipment.

“What we’re doing right now is taking that perception system and moving it over onto the DOT frame. That will allow the DOT system to move from what is currently a semi-autonomous or supervised autonomous state, to eventually one of being full autonomy,” Robey said.

He said the system will eventually be able to co-ordinate multiple DOTs on the same field while they execute a precision ag prescription.

While this does mean that ownership of the technology moves to the US, manufacturing and development of Dot will continue in Regina and Saskatchewan (in addition to the Dakotas).

Similarly Dot machines are starting to be used in more locations.

“Our initial target will be Western Canada. That’s where DOT and SeedMaster have generated the most interest and have had the most demonstrations of the DOT platform. But this year we plan to place a few units with select partners around the world.”

For example there’s now one active in Southwest Ontario:

Here is what @SeeDotRun looks like, running! Just crossed the 50 acre mark on this farm. Online UT viewing of scale, rates and speed. @RavenPrecision pic.twitter.com/gcOaq2iJab

— Chuck Baresich (@TheSandFarmer) May 15, 2020

Similarly Dot will be used by this Canadian agricultural college to further study autonomous agricultural technology.

Olds College is excited to announce that we are the only post-secondary institution in the world to deploy the fully autonomous DOT Power Platform as a teaching and research tool on the #OCSmartFarm

— Olds College (@OldsCollege) April 28, 2020

Read all about this exciting addition to our Smart Farm: https://t.co/A7jGTc32kA

Although at the time of writing this their website is down, so perhaps that college also needs an IT program as well? :P

Finally, here’s a post from reddit from a Dot user that also served to remind me to write this issue of the newsletter.

I spent the long weekend thinking about agriculture and technology, in an attempt to both distract myself from the pandemic, as well as anticipate how to pivot professionally. I hope you enjoyed this modest foray into the world of autonomous agriculture. It’s a subject I suspect I’ll be writing more about in the weeks and months to come.

Dot helping out a neighbor finish off seeding his Barley last week in White City, SK.#ravenautonomy #autonomy #farming #precisionfarming #dotautonomy #ravenprecision #precisionag pic.twitter.com/HlzAH1v5vZ

— Raven Precision (@RavenPrecision) June 12, 2020