Increasing food security while decreasing barriers to entry

Historically speaking, our food supply was distributed. Communities largely produced their own food, and individual households often participated directly. The small towns outside of major cities acted as hubs in a larger agricultural and food production network.

However over the past several decades agriculture has seen similar consolidation and concentration of ownership as has happened in all other sectors. Global supply chains have replaced local ones, and the food we eat and the business behind it is dominated by global corporations.

Pre-pandemic this wasn’t perceived as an issue by most people, as they were getting cheap food, when they wanted, with a wide variety of selection, regardless of the growing season. However now that we’re in the thick of it, and the timeline for this crisis is currently measured in months (if not years), the attention paid to our food supply is understandably increasing.

In particular the current system is remarkably brittle. It does not seem to be flexible enough to handle adverse conditions, and changes in demand and the marketplace as a whole threaten significant elements of it. On the one hand we saw empty store shelves in response to panic buying, now replaced with rationing of paper products, cleaning products, flour, meat, and others. On the other hand, many agricultural producers are now having to destroy food rather than distribute it, because the demand and delivery channels are out of sync.

Mushroom farmers have too many mushrooms. South of Ottawa, one farmer was forced to destroy 20,000 pounds, filling the mushroom houses with steam so hot nothing could survive: https://t.co/Ljmw1zodfB

— Jake Edmiston (@jakeedmiston) April 16, 2020

The article above is one of many that describe the current paradox in our food supply. Over production based on demand that has disappeared and distribution that is unresponsive means that a significant amount of food is being wasted. Milk being dumped, eggs being tossed, and mushrooms being destroyed. Not because the food is bad, nor because people have stopped eating, but because that food cannot be connected with consumers in a configuration that currently works.

Most of this wasted food was destined for restaurants, hotels, and other businesses now closed or drastically reduced. The supply chain is not responsive enough to pivot and redirect that food to other channels. In the case of the mushroom growers above, it is largely an issue of packaging, which seems like a poor excuse for destroying food, but is a reflection of the dysfunction of the food supply system.

However it’s not just how food is distributed, but also how it is processed. For example the relative centralization of the meat industry has left it particularly vulnerable to this pandemic:

Great reporting from Des Moines Register about the uh-oh situation in Iowa's 18 meat processing plants.

— Rachel Maddow MSNBC (@maddow) April 16, 2020

- Major outbreaks at plants in Louisa and Blackhawk Counties.

- Tama plant closed last week for COVID.

- More cases at a JBS plant in Marshalltown...https://t.co/lpMCkju6kK

In 1967, there were 9,627 meatpacking plants in the U.S.

— J.D. Scholten (@JDScholten) April 11, 2020

Today, there are just 1,100.

During a pandemic, when a few workers get sick, it has a massive ripple effect on our food supply. WE NEED TO ENFORCE ANTITRUST LAWS. https://t.co/TJFYrn9TLL

The irony of course is that it doesn’t have to be this way. Of all of the supply chains that have been globalized, food may be the easiest to redistribute, and food security seems like a significant issue to use as a justification to do so.

As someone who recently moved to a relatively rural location located in an active agricultural region, I’ve been learning lots about where our food comes from and how it is produced. We have a big garden, our own chickens, and goats. We’ve also been sourcing other direct suppliers. I buy flour direct from a mill, maple syrup direct from a sugar shack, and my response to this potential meat shortage was to talk with my neighbour about sourcing and splitting a whole pig. We also plan to start raising rabbits for meat.

All of which got me thinking what role transparency and accessibility could play in helping to transform our food supply chain into one that is more resilient and responsive.

Imagine a system where anyone could browse activity ranging from agriculture to retail. An open marketplace that combined global supply with local demand.

This isn’t about ending global supply chains, but rather making them more responsive, and allowing local supply chains to be just as competitive. It should be cheaper for example to buy local rather than buying global, given transportation costs, but growing seasons and volume will continue to keep global supply relevant.

The key is achieving both transparency and accessibility. Transparency in the sense that all are able to see and monitor activity, and accessibility in that you lower as many barriers to entry as possible.

For example this accessibility can be achieved by combining education with standards or regulatory frameworks.

On the one hand we now have knowledge platforms like YouTube and social media where just about anyone with access can learn how to prepare any food imaginable. The same is true with agriculture and raising food. The knowledge is out there, and should be made readily accessible.

On the other hand, standards and regulatory frameworks can ensure that the food is prepared safely, or that agricultural practices are employed responsibly. It should be possible for someone to prepare food for sale in their kitchen, as long as they are meeting the same standards for a restaurant or commercial kitchen, scaled down of course to their level and facilities.

These regulations and standards do not need to be onerous or an obstacle to people participating in the marketplace. Rather they can be combined with transparent and responsive systems that ensure health and consumer protection.

The concept of traceability has been circulating in the food industry for some time, and is now becoming more feasible thanks to increases in data management and tracking capabilities, in particular associated with distributed ledger and blockchain tech.

IBM has been a big proponent of traceability and responsiveness in the food chain, and has been doing quite a bit to build and implement systems that make it possible. Here’s a brief video that describes some of their (proposed) work:

However transparency and accessibility is not just about traceability. It’s also about reputation. The restaurant industry has already been transformed by reputation and rankings, as has the smaller but still relevant recipe (blogging and influencer) industry. Therefore a distributed system is only as healthy or strong as its reputational framework and ranking system.

This combination of standards, traceability, and reputation could enable a truly distributed food supply that allows large and small actors alike to not only co-exist, but flourish in a system designed to ensure resilience, responsiveness, and redundancy.

Such a system could nurture a far healthier and smarter capacity that rewarded people for developing expertise throughout the food supply chain. Having a system that encouraged and rewarded small and medium players fosters a flexibility that we need to thrive amidst the chaos of crisis or impending crisis.

For example, imagine the current situation with dairy over supply. Pretend for a moment that the issue was not supply side management, but rather a shift in the economy as has happened. Dairy producers are meeting the needs of restaurants, said restaurants close, and all of a sudden they have excess capacity.

If there was a transparent and accessible marketplace, those producers could turn around and offer the milk to the open market. In this context, I am imagining a platform, that was federated and integrated, so that it acted like say Facebook, where we’re all on it, but remained a collection of independent sites and services.

Due to the over supply, the milk should be priced at a discount. This is meant to incentivize its repurposing. Either the demand is high enough, that a distributor, or person with a tanker truck, is willing to pick up the milk, and distribute it. If demand is not high enough, the price should be lower, and if low enough that the distributor can pick it up and still make a profit doing something with the milk.

To be clear, this is unprocessed and unpasteurized milk. Hence if existing processors are not interested or willing to take it, it would otherwise be dumped. Yet what if smaller producers were willing to pasteurize it. After all you can do this at home with a pot on a stove (or instant pot). How cheap would the milk have to be for you to be willing to do this? Maybe your neighbour would do so and share with the ‘hood if the price point is accessible enough? Or use the milk to make yogurt and then resell the yogurt (if the margin makes it worthwhile).

Making food is not actually hard, and if the incentives are in place for people to do it themselves or for their area this kind of distributed production can be viable.

The enabler is the transparent and accessible marketplace, a/k/a the digital platform that makes it all possible. It’s what unites small and big players in the same market, and enables opportunities when it comes to growing and selling food.

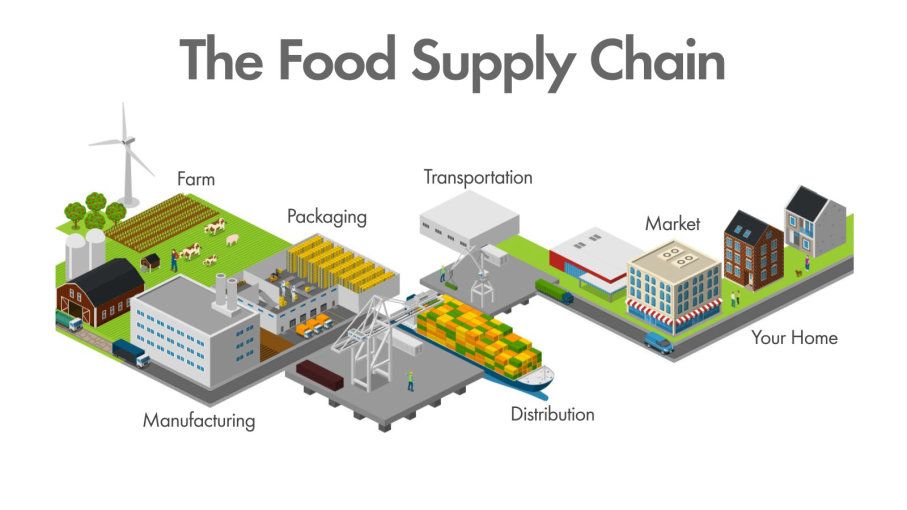

For example, check out the following image:

What if any part of this chain could be performed by a small or medium organization? What if you could grow potatoes and sell those potatoes easily to your neighbours and nearby residents? Or if the demand merited, aggregated and shipped around the world?

What if one or two days a week you sourced flour from a nearby mill or oats from nearby grain silo and used them to make baked goods or granola that you then sold for a modest profit? Nobody does it the way you do, at least locally, and that’s the value you bring to the market?

Similarly some people like making food, and others not so much. Rather than rely exclusively on restaurants (many of whom have unstable business models) what if we had a range of options for prepared food, from Michelin star chefs to grandmothers down the street.

Once you scratch the surface of food production, this is how a lot of it works, it’s just not accessible to most people, and it’s not as transparent as it could be, so as to allow more producers and consumers to make informed choices.

Similarly you might own a truck, and are able to use that truck as part of local and regional logistics. No need to be part of a fleet, what if you could make more money as an independent, working when you want, hauling what you want, reacting to the value and demand in the open market?

If we acknowledge the extent to which the Internet has already transformed our society, we can reflect on how networks transform production and distribution methods, enabling more accessible and participatory systems.

There’s no reason our food supply chain has to be brittle and prone to failure. The more of us who participate in the production of food the more food (and food choices) there will be for us to consume. Diversity of scale will help foster diversity in our diets and prosperity throughout our economy and society.

The more knowledge we have about our food system the stronger our food system will be. In this time of pandemic, what we eat should not be taken for granted, we have a unique opportunity to reassess where our food comes from, and how we can ensure nobody goes hungry.