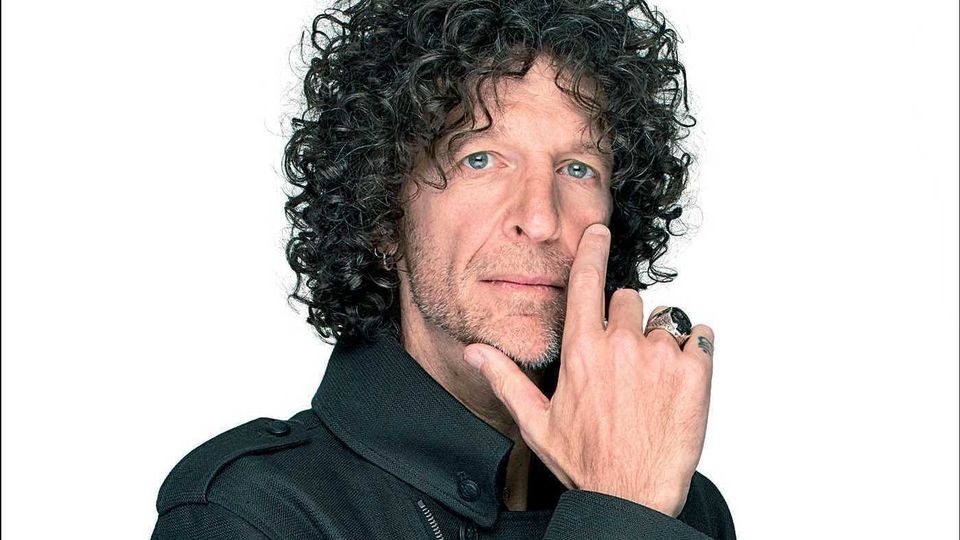

What would Howard Stern do?

The missing link in this crisis is effective public health education. While we may be seeing the largest public health campaign in recent history, it is not achieving a desired or necessary outcome.

The obvious manifestation of this is the current attempts to reopen society, which if we are to believe epidemiologists (and I do), will only result in the further spread of this virus. Awareness, let alone compliance with public health advisories, is shockingly low, and I fear that the legitimacy of public health officials and their advice is diminishing.

Rather than address or adjust this failing, politicians are turning to technology for solutions, whether in the form of surveillance based apps, or an increasingly false hope that testing and vaccines will save us.

However if we are to reinforce our commitment to democracy, than we ought to double down on our belief that the answer is public health education, i.e. earning the trust and consent of people, rather than demanding their obedience.

Yesterday I had a thoroughly enjoyable conversation with writer, editor, and Metaviews subscriber Chris Frey, who’s also a contributor to the Buckslip newsletter.

Chris asked me what I thought public health agencies could be doing better, and I flippantly suggested that they ought to have hired Howard Stern to help with their messaging. It was a comment partly made out of frustration, but as I thought about it further, it kept making more sense to me.

To be clear, I am not a Howard Stern fan per se, but as a media scholar, I’ve definitely studied him, and he deserves recognition as an innovator in the field of interactive broadcasting.

Howard has incredible skill and talent reaching a diverse and often ignored constituency. Initially he did this as a shock jock, using humour, and pushing the lines of what is acceptable on terrestrial radio. However in the latest stage of his career, on satellite radio, he has also demonstrated his abilities as host and interviewer to connect with his audience, and his guests.

Part of Howard’s appeal is that he eviscerates the bullshit that permeates the media industry, while also emphasizing the vulnerabilities and flaws that we all have. There’s an intimacy that Howard cultivates on his show and with his fans that fosters an authenticity and trust that remains relatively rare in a media environment of pervasive phoniness.

This is relevant for public health agencies, as they are now, for all purposes, broadcasters. This is true of public health officials, who now find themselves on TV every day, providing updates, but it is also true of their organizations, who are now broadcasting updates via social media and legacy media. I say broadcasting on social media because you can safely assume they’re not engaging in debates.

Unfortunately, due to the dynamism that is scientific research, these public health agencies have and continue to offer contradictory information. For example I’m still waiting and hoping that they will more strongly encourage if not mandate mask wearing.

However the problem with broadcasting is that it does not make it easy to be contradictory or change your mind. That’s where interactivity, or interactive broadcasting has an important role to play. It offers the opportunity to explain why positions have changed, or why they need to evolve over time.

For example Howard Stern, like any human being, changes all the time. To a large extent his fans not only afford him this human quality, but also encourage it. An effective and skilled interactive broadcaster is afforded the characteristics and shortcomings of being human.

Howard also understands the power of the vernacular. This is partly why his shows have always involved profanity and vulgarity, even when they were broadcast on terrestrial radio. He sounds and speaks like his audience, and that makes it easier for them to both understand and identify with him. While that may be a reflection of NYC and its strong oral traditions, it still offers insights for public health officials struggling to get and maintain the public’s attention, let alone earn their trust.

When public health officials use the language of medicine, and speak to the public as if they were speaking to a university educated audience, they immediately turn off and alienate a large segment of their population (of which I include myself). Not all public health officials are guilty of this, but it does reflect the culture of medicine, which struggles to use language accessible to the lay person.

In contrast, conspiracy theories, while sometimes incoherent for their own reasons, do tend to use the vernacular, and language that is accessible and inclusive.

Employers Rush to Adopt Virus Screening. The Tools May Not Help Much. https://t.co/wEcDKJqQLK

— Dan Schwartz (@danielschwartz) May 11, 2020

Mr. Grewal is one of many business leaders racing to deploy new employee health-tracking technologies in an effort to reopen the economy and make it safer for tens of millions of Americans to return to their jobs in factories, offices and stores. Some employers are requiring workers to fill out virus-screening questionnaires or asking them to try out social-distancing wristbands that vibrate if they get too close to each other. Some even hope to soon issue digital “immunity” badges to employees who have developed coronavirus antibodies, marking them as safe to return to work.

But as intensified workplace surveillance becomes the new normal, it comes with a hitch: The technology may not do much to keep people safer.

Public health experts and bioethicists said it was important for employers to find ways to protect their workers during the pandemic. But they cautioned there was little evidence to suggest that the new tools could accurately determine employees’ health status or contain virus outbreaks, even as they enabled companies to amass private health details on their workers.

My local public health unit continues to encourage people to see masks as voluntary and not necessary. As a result, few people at the grocery store I go to, including staff, wear masks.

Where a broadcaster doesn’t really care, or know, if their message is being received or having the intended effect, an interactive broadcaster would, because they’re interacting, and as a result, tend to have a stronger connection with their constituency.

Given the projected length of this pandemic, there’s time for public health education to evolve. There’s hope that public health officials will recognize the extent to which they are losing the campaign to make friends and influence people, and need to reassess their tactics and strategy. The consequences of not doing so will literally be lethal.

After my conversation with Chris Frey yesterday, I participated in an event hosted by Paolo Granata for the McLuhan and media ecology crowd. I took the opportunity to share some of my thoughts about what we could learn from Howard Stern, and it was met with relative hostility. It took a while and quite a bit of effort just to get the other participants to understand let alone consider what I was proposing.

Academics do tend to have difficulty seeing past their own perspective, and my concern is that public health officials suffer from the same cognitive constraints.

In the battle between the vernacular and the vocabulary of the expert, the vernacular will always win. If we are to lament the decreasing authority and credibility of the expert, we should not blame the audience, but rather look to the formal language of the expert, and recognize how it alienates the audience rather than empower them.

If the expert wants to be respected and listened to, they should embrace the vernacular, if not also the profane, and use the language and culture of their audience, rather than the elitist trappings of institutionalized expertise.

Granted it is a bit of a paradox, as the expert probably thinks that their expertise was granted to them by an institution, whereas I argue that their expertise is a reflection of their knowledge and wisdom.

This means that if they cannot share that knowledge and wisdom, by communicating with people using clear language, then there’s little chance their expertise will be recognized or respected.

What I find encouraging about this crisis is that in breaking society, we are also seeing the dissolution of a lot of bullshit. A lot of the myths we used to cling to are rapidly falling apart. My favourite is that remote work is not viable, when in many cases it is not only desirable, but fare more efficient.

I highly recommend watching the video below, which I feel proves my point.

Still having the company meetings online. pic.twitter.com/aR3LfuSdKl

— Andrew Cotter (@MrAndrewCotter) May 11, 2020

All jokes aside, we can do better.