Giving people greater agency and control over their data

Over the last decade, data literacy has grown substantially, and along with it the growing awareness that data is a valuable commodity. This has not only fostered an unhealthy obsession with data in this current crisis, but it has also changed the relationship most people have with data in general.

Our last few issues have touched upon this relationship with data, last week citing research that shows health data is inherently subjective, and yesterday that data is insufficient without narrative.

In today’s issue, let’s explore the potential for people to have greater agency and control over their data. Can the collection and use of data be democratized? Can a democratic society collect and use data responsibly, and with the consent of citizens? Can people have greater access and input on how their data is used and why?

Is it possible to reverse the sense of helplessness and alienation that most people have with regard to their data? Can they take back control over how their data is used? What role is there for a data commons?

This is the goal of DECODE, a European project that “provides tools that put individuals in control of whether they keep their personal information private or share it for the public good.”

We mentioned DECODE at the end of our Future Tools issue on Decidim. The two are siblings, born from the democratic smart cities movement which emerged from Barcelona and Amsterdam.

When smart city technology and IoT (Internet of Things) based surveillance was deployed in Barcelona in 2011, most citizens did not know or understand how this technologies were being used. However when a new municipal government was elected in 2015, they saw smart city technology as a path towards increased municipal participation. Decidim was an example of using technology to include more people in decision making, and DECODE was designed to increase data literacy and include more people in the broader milieux of data science.

DECODE is not just about protecting privacy or giving people the ability to protect their data, but it is also about enabling better (and more responsible) use of that data. On the one hand this means privacy frameworks that ensure the use of that data is secure and protected, however it also means that civil society groups and able individuals can use that data for their own initiatives or campaigns.

If we entertain the notion that a data driven society is desirable or democratic, then we have to ask who’s data is doing the driving, and for what purpose? Creating a system that not only empowers citizens to protect their data, but also assists in their ability to use that data to participate in political and policy debates, offers us a glimpse as to how a data driven democracy could work.

DECODE is an experimental project to develop practical alternatives to how we use the internet today - four European pilots will show the wider social value that comes with individuals being given the power to take control of their personal data and given the means to share their data differently.

DECODE will explore how to build a data-centric digital economy where data that is generated and gathered by citizens, the Internet of Things (IoT), and sensor networks is available for broader communal use, with appropriate privacy protections.

As a result, innovators, startups, NGOs, cooperatives, and local communities can take advantage of that data to build apps and services that respond to their needs and those of the wider community.

The above is from the DECODE website. Their general focus is to combat the rise of black box governance, i.e. the use of opaque automated decision making, by creating a system that combines transparency with user agency.

This is relevant not just because we live in a data obsessed society, but in particular because of the way data is being used in this crisis, and how data collection is poised to dramatically expand as a result of it.

A wave of companies are trying to sell tracking accessories to business owners eager to reopen under the aegis of responsible social distancing and to governments hoping to keep a closer eye on people under quarantine. https://t.co/lEuDf05B2E

— The Intercept (@theintercept) May 26, 2020

The above article is but on example of the kind of technology now emerging or being repurposed. It’s comical if it also wasn’t kinda dystopian.

However it illustrates the kinds of (get data fast) schemes that are currently fashionable.

Pandemics and big data tyrannies

— LSE Business Review (@LSEforBusiness) May 11, 2020

Tyranny typically occurs when citizens share their data (willingly) to achieve safety but end up losing control of it. @FerasBatarseh @GeorgeMasonUhttps://t.co/ebJUjwxUFH

Moreover, the current proposed solutions to the virus, including contact tracing, easing of e-health records restrictions, smart-phone tracking, and e-temperature measurements would create big amounts of data but pose many critical questions: Who owns the health data generated by tracing? Who manages the data generated by tracking? Are they selling it to third party vendors? And how are they protecting the data infrastructure from computer viruses and hacker attacks? As global interconnectedness continues to grow, more and more people are finding themselves living in a data republic. A republic that ought to be democratised, but a typical case of big data tyranny occurs when citizens share their data (willingly) so they can achieve safety and good health. The wisdom of Benjamin Franklin states that: “Those who would give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety, deserve neither”. Once we give up our data liberties, digital social distancing would not be a choice only during exceptional times, rather, an unavoidable reality of electronic isolation and easy targeting.

Data democracy allows personal data ownership, makes data available to citizens, and reduces costs to popularise, disseminate, and crowd-source data. The opposite of that (i.e. a big data tyranny), is a centralisation of all personal health datasets in the hands of few companies or entities that have not been chosen by data creators. That notion dictates the transformation of the famous saying “data is the new oil” (indicating the rising power of data in the global economy) to “data is the new blood”.

Clearly the DECODE project and the role of data commons is now even more relevant and necessary.

New DECODE report❗

— Decode Project (@decodeproject) January 29, 2020

'Common Knowledge: citizen-led data governance for better cities'

Read about:

➡️ impact of the DECODE pilots

➡️ recommendations for policymakers

➡️ 3 ‘ready-to-implement’ use cases for data commons in citieshttps://t.co/uMxKbrE6Xb pic.twitter.com/Xv7Jt8SCjO

The types of value extracted from personal data will be one of the defining questions of the future digital economy. Currently too much data is either misused – hacked, exploited or used improperly – or under-used – restricted to very narrow financial conception of value. As data becomes more and more intimate, our ability to respond to these problems will become even more important. Taking the concept of the commons and applying it to data is a useful way of addressing these twin problems. Much of the practical application of DECODE’s technology to date has focused on moving the idea of a data commons from theory to practice. This report is a summary of that work.

Commons provide a useful set of principles to support privacy-enhanced sharing of data for public value, with the aim of reconciling both personal and collective control, while maintaining transparent, accountable and participatory governance over data.

The report lists a wide range of different data commons and the kinds of applications that serve them. It’s these applications that help give life to the concept, and were the focus of the recent pilot projects completed by DECODE in concert with Amsterdam and Barcelona.

In Amsterdam, one pilot project was an Anonymous Proof of ID. We’re often asked for ID, whether to buy liquor, cannabis, or to prove we are who we are. This pilot project sought to upgrade the concept so that the verification could happen without actually disclosing who the person is. While this project was focused on young people proving they were old enough to enter a bar or club, could it also be applied to COVID passports and the status of our health in relation to the virus?

The second DECODE pilot project in Amsterdam was an “ethical and locally owned social network” called GebiedOnline (GO). The goal was to move the public spaces that communities use to connect online from private companies like Facebook to data commons where the community controlled both the platform and the data. And, unlike Facebook, participation did not require the disclosing of personal information, as the authentication system, similar to the first pilot project, was able to authenticate users without disclosing personal information (unless desired).

In Barcelona, the two pilot projects were the Digital Democracy and Data Commons, which featured the Decidim platform we discussed in a past issue, as well as the Citizens’ Internet of Things Data Governance, which encouraged citizens to examine and understand how their smart city worked. This included everything from energy usage, to traffic patterns, city works, and the delivery of public services. In helping people understand how their city operated, residents were then encouraged to participate in decision making and the development of new initiatives.

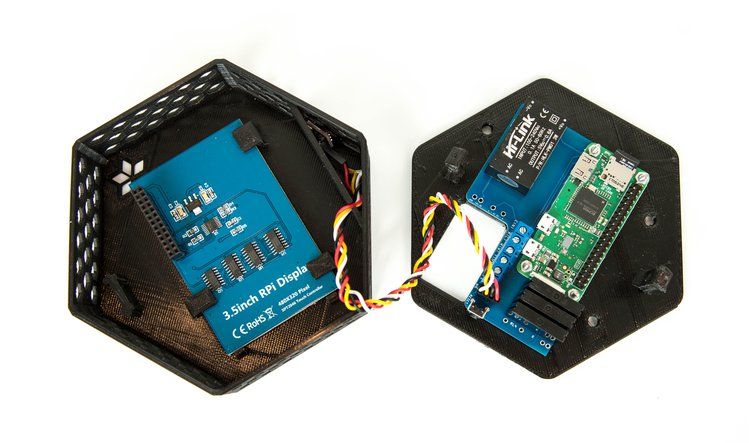

Of course in order to have effective participation the citizenry require a certain level of data literacy. Initiatives in Barcelona and Amsterdam sought to help “onboard” residents to give them the tools and knowledge to be active participants. This includes online courses, videos, but also physical spaces like Fab Lab Barcelona that helped people build their own Smart Citizen Kits:

From the Smart Citizen Kit website:

The Smart Citizen Kit is the core of what we call the Smart Citizen System: a complete set of modular hardware components aiming to provide tools for environmental monitoring, ranging from citizen science and educational activities to more advanced scientific research. The system is designed in a extendable way, with a central data logger (the Data Board) with network connectivity to which the different components are branched. The system is based on the principle of reproducibility, also integrating non-hardware components such as a dedicated Storage platform and a Sensor analysis framework.

On top of that, the system is meant to serve as a base solution for more complex settings, not only related with air quality monitoring. For that purpose, in addition to the Urban Board, the system also provides off-the-shelf support for a wide variety of third party sensors, using the expansion bus as a common port. One example is what we call the Smart Citizen Station: a full solution for low cost air pollution monitoring.

This gets back to the larger question of who’s data is being used? Clearly democracy must involve making it possible for citizens to collect their own data,

It’s also worth noting that Barcelona created another free and open source tool called Sentilo to help in the IoT Data Governance project.

Sentilo is the piece of architecture that isolates the applications that are developed to exploit the information “generated by the city” and the layer of sensors deployed across the city to collect and broadcast this information.

The Barcelona City Council, through the Municipal Institute of Informatics (IMI), started in November 2012 a project conceived for define the strategy and the necessary actions in order to achieve global positioning Barcelona as a reference in the field of Smart Cities.

Sentilo is an open source sensor and actuator platform designed to fit in the Smart City architecture of any city who looks for openness and easy interoperability. It’s built, used, and supported by an active and diverse community of cities and companies that believe that using open standards and free software is the first smart decision a Smart City should take.

DECODE uses distributed ledger technology (DLT) to create a data commons that individuals can interact with securely, while also maintaining their privacy. Blockchain technology is a DLT, however DECODE uses Chainspace, which is an alternative to blockchain that focuses on auditability. The following is from a post from one of the DECODE funders describing how this technology works:

Achieving transparency through decentralisation, while upholding individual privacy of people using the network, might feel like two competing aims. However, thanks to advances in modern cryptography, it is possible to ensure that operations were correctly performed on a ledger without divulging private user data – a family of techniques known as zero-knowledge. This brings us to our third defining principle.

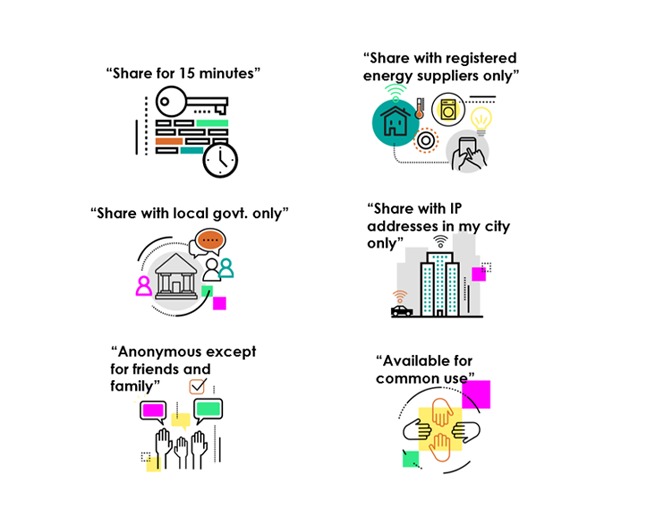

They also have an image that illustrates some of the features people would have when it comes to controlling how their data is shared:

DECODE is a fantastic example of what’s possible when democratic concepts are translated into technology with a clear focus on the citizen rather than the state. One of the tyrannies of our current technology and data regimes is that users assume they have no alternatives, nor no other way of using the technology (and data).

Part of the point of Future Tools is to show that their are alternatives. In this case, the alternatives are quite compelling.

It’s also worth noting that one of the by-products of DECODE has been the emergence of the Cities Coalition for Digital Rights, of which Barcelona and Amsterdam were founding signatories.

As cities, the closest democratic institutions to the people, we are committed to eliminating impediments to harnessing technological opportunities that improve the lives of our constituents, and to providing trustworthy and secure digital services and infrastructures that support our communities. We strongly believe that human rights principles such as privacy, freedom of expression, and democracy must be incorporated by design into digital platforms starting with locally-controlled digital infrastructures and services.

As communities increase their digital literacies and take greater control and agency over their data, they will be in a far stronger position to serve their citizens and tackle whatever crisis they may face.

After learning about DECODE and some of the potential it holds, it makes me wonder how we could have handled this crisis if our respective governments and societies were in control of their data rather than beholden to it?

Could our response to this crisis have been more effective, responsive, reasonable, and measured, if we not only had the capacity for better data driven decision making, but more importantly if that capacity was democratized. If we had put in the work to foster greater literacy, empower people with better tools, and nurture a culture of distributed data driven participation.

Although maybe it’s not too late? Maybe there’s still time to think about the role of a data commons approach to the surveillance proliferating as a result of this pandemic?

Barcelona is leading the fightback against smart city surveillance | WIRED UKhttps://t.co/4ufwWwUtMM pic.twitter.com/N4ZVscbwgs

— Jesse Hirsh (@jessehirsh) May 23, 2018